Two sides of web application. Part 1: the tools

Prologue

How do we usually create a web application? We run a bootstrapping script, which provides us with a skeleton of our application and then we just extend it with the features we need.

That's exactly what we did at the last hackathon we were attending - we started with rails new twf and spent half of the day integrating our blank app with Angular, Paperclip, creating API methods and so on. But the effort we needed to accomplish our goal (quite a simple web app) was really huge.

So I decided to find the best combination of backend and frontend technologies that would cause less pain.

At the project I was recently introduced to, the line between frontend and backend is distinguished very clearly: we have an API, written in Clojure and thin frontend application, made with Angular that works on a generated set of static assets - HTMLs, CSS and JS files (but under the hood we are using HAML and SCSS).

The application I will be implementing throughout the whole article has the same architecture: it has RESTful API and MVVM on the frontend, made with Angular. I welcome you to the journey of research and new technologies!

Why not go with Rails?

Because Rails is often overused. Especially if you install all of frontend libraries (like Angular, Bootstrap, some Angular plugins, etc.) as RubyGems. Frontend should stay on the front end of the application; you should not lock your application at some precise version of the JS script, provided by a gem and rely on author's way to integrate it with Rails.

In our case, Rails is too heavy - when all you need is database + routing + a couple of lightweight controllers, all Rails' features will become a ballast to our app, which must be small, by design.

The goal

Before we start, let's think of what we'll be creating. Will it be a web shop? Or a blog? No, we need something outstanding! Something we've done never before...

After an hour of imaging what it may be, I decided to go with web analytics tool. A prototype, which will be able to tell how many visitors your web application gained recently.

It shouldn't be too complicated, because, you know, it's just a tutorial... So we'll be tracking users' location and browser only. And we'll be displaying those analytics as a chart (values like total visitors, browser usage) and in a table (the same info as the chart).

Architecture preview

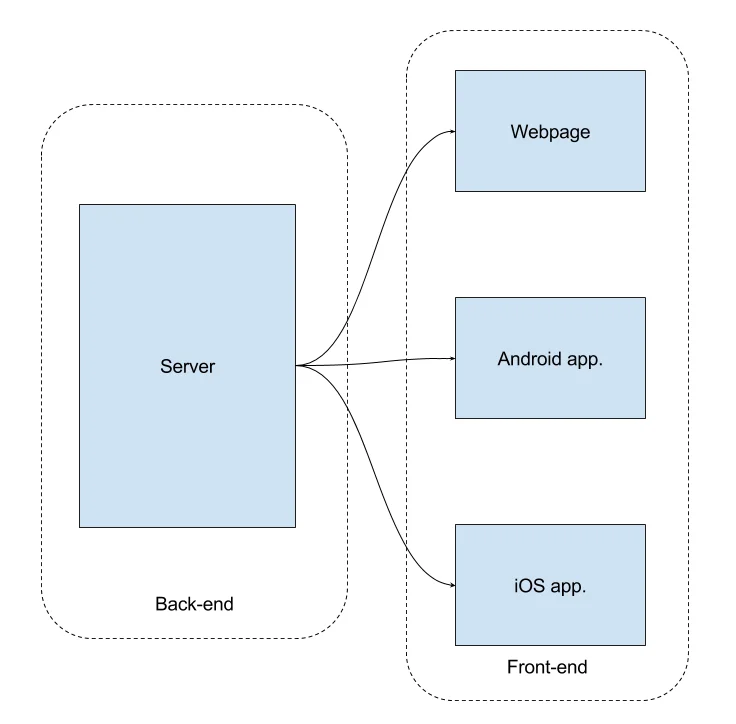

We will be developing our application with two layers (or two sides) - front-end and back-end:

The front-end part is the one the user sees and uses - the web page, mobile or desktop application. The back-end part is the one, which does all the magic - prepares data for the front-end side to display, performs data operations as a reaction on user's actions, etc. Thus we could easily replace either the back-end part or the front-end one or even both and replace them with all brand-new implementation. This architecture allows us to do that really easily.

Build with the right tools!

Now, since we separated our frontend part of application from the backend part, we may use different preprocessing languages to write stylesheets and views. And even controllers! So let's take the most from 2015 and use the newest tool set: Jade, ES6+ and SCSS. And put them all together with Bower and Gulp.

All those Jade, SCSS and ES6 are not supported by a browser out-of-the box. They must be compiled to HTML, CSS and JS in order to be recognized by the browser. But they are here to help you writing code quickly. I listed some of their key features below.

Jade

Jade is a template rendering engine with its own markup language. It is somewhat similar to Haml and Slim - it nests XHTML nodes with indentation, closes tags automatically... But it is especially good at writing complex web pages, consisting of layouts and partials.

Layouts are big templates, containing placeholders, where concrete partials will be placed. So, for example, you may create a separate layout for your webshop' landing page, account page and shopping cart. They will be different. And all of them will use different sets of partials. But, for example, a footer and a quick shopping cart preview or user account widget (the one with a link to user's account page) will be the same. To prevent duplicating those widgets' code on each of the layouts, we extract them to separate files, called partials and then just make a reference (a placeholder) in our layouts, saying "place that partial's content here".

In case of Jade, we may override or extend existing partials in a layout, without touching partial's file itself. So, for example, if we want to make user's avatar to be shown in a user account widget only on a product page, we just override user widget partial on a product page, removing the part with the avatar.

SCSS

SCSS is a way to simplify writing CSS. It is so simple, yet so powerful, that you will fall in love with it after the first few stylesheets! See, in CSS when you write a long selector, specifying many parents, you may find your stylesheets ugly and huge, when describing different children of one, deeply nested parent.

So, let's say you are having a user widget. And it may be placed both on page's header, footer and sidebar. But

the avatar image will look differently on each of those - it must be smaller in header and footer. So you

start writing selectors like .sidebar .user-widget .avatar img and .header .user-widget .avatar img.

That's painful, but not that much, if you have just a couple of those. However, as your website grows, you

start getting really, really upset about that.

And here's where SCSS is just a revelation: its great power is in its selectors, variables and mixins.

Selectors allow you to describe selector' nesting just as you'd be writing C code:

.header {

// header styles

.user-widget {

// header user-widget styles

.avatar {

// maybe something differs in avatar itself?

img {

// ah! here's it!

}

}

}

}Variables allow you to get rid of all those magic values. So if you use one color many times across your styles, you just extract it into a named constant and use the pretty named value everywhere!

Mixins allow even more: you may extract the parts of the styles into a named and even parametrized function!

Relating on all of those, you may re-write your user widget as follows:

$header-avatar-size: 50px;

$sidebar-avatar-size: 150px;

@mixin avatar($avatar_size) {

max-width: $avatar_size;

max-height: $avatar_size;

}

.header {

.user-widget .avatar {

@include avatar($header-avatar-size);

}

}

.sidebar {

.user-widget .avatar {

@include avatar($sidebar-avatar-size);

}

}Gulp

I found Gulp to be super-easy for tasks like compiling stylesheets, views and javascripts. But before

we continue with Gulp, let's initialize an NPM project with npm init and install the plugins required:

npm install -g gulpAnd Gulp plugins:

npm install --save-dev gulp gulp-babel gulp-scss gulp-jadeI will describe how Gulp works and how we can use it in our project in a minute. For now, let's just install the frontend dependencies.

Bower

Let's fix our frontend on specific versions of frontend libraries, so when we update the whole project, nothing gets broken. To make our development quick, we’ll use Twitter Bootstrap. All the frontend dependencies will be managed by a tool called Bower.

Bower is a tool like npm, but used strictly with frontend libraries like jQuery, Angular, Twitter Bootstrap and many others. It's important to keep frontend libraries separate from the backend ones, so we can keep our backend application completely separate from frontend one.

Bower comes with a command-line tool, bower, which we'll use to fill out the bower.json file. It is used by Bower to specify which libraries does our application require:

npm install -g bower

bower init

bower install --save bootstrap angularThese commands create a directory bower_components, containing all the dependencies installed, each in its own sub-directory. With that in mind, we'll be referencing our frontend dependencies, relatively to their catalogs within the bower_components directory.

Now let's write a build task for Gulp. Gulp is a streamed build tool. That means, that each operation you perform, passes its result to another operation as the input argument. So, for example, if you run gulp.src('src/styles/*.scss'), it'll return you an object with the list of all the SCSS files and the magic pipe() method. And when you call the gulp.src(...).pipe(scss()), Gulp will pass that list to the SCSS compiler plugin, so you will get a compiled CSS code. That is, not a CSS file itself, but a compressed, merged, CSS file' content.

And that describes the second important feature of Gulp: it does not store the intermediate operation results. It is almost like a functional programming - you just have the input data. Then you call a chain of functions on it,

passing the result of one function call to the next function as its input. Same happens here, but in

a manner not that strict - since we are using Javascript, we can store the intermediate results in the memory. But to store

the results in the files, we should pass them to the gulp.dest(...) function. Depending on the function, looking

to store its results, gulp.dest() may point to a directory or a single file, where the results will be stored.

Below is our first Gulp task. Write this code in the gulpfile.js:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

sass = require('gulp-scss'),

babel = require('gulp-babel'),

jade = require('gulp-jade');

gulp.task('build', function () {

gulp.src('src/views/**/*.jade')

.pipe(jade())

.pipe(gulp.dest('public/'));

gulp.src('src/javascripts/**/*.js')

.pipe(babel())

.pipe(gulp.dest('public/javascripts'));

gulp.src('src/stylesheets/**/*.scss')

.pipe(sass({ style: 'expanded' }))

.pipe(gulp.dest('public/stylesheets'));

});This tells Gulp to define build task, which compiles all the Jade, SCSS and ES6+ files into HTML, CSS

and JS files, correspondingly. Compiled files are placed within the public/ directory, so we may

easily render them with almost any web-server. But first things first, we need to prepare directory structure

like this for our task:

.

|____bower.json

|____gulpfile.js

|____package.json

|____public

|____src

| |____javascripts

| |____stylesheets

| |____viewsThis may seem odd to the paragraph, dedicated to build tools, but let's check how our tasks work.

To do this, we need to write some test files to check our build task. So let's create one of each kind:

src/views/index.jade:

html(lang="en")

head

meta(charset="UTF-8")

title OurStats

link(rel="stylesheet" href="/stylesheets/main.css")

script(type="text/javascript" src="/javascripts/main.js")

body

h1 Hello, world!src/stylesheets/main.scss:

h1 {

padding: 0 10px;

border-bottom: 1px solid #dedede;

}src/javascripts/main.js:

function timeout(ms) {

return new Promise((res) => setTimeout(res, ms));

}

async function f() {

console.log(1);

await timeout(1000);

console.log(2);

await timeout(1000);

console.log(3);

}

f()And to actually check our task, we need to run it with

gulp buildNow, you may open the HTML generated from Jade in a browser, but it'll look ugly, because your

browser will doubtfully find stylesheets and javascripts that easily. To make the magic happen, we

will use another Gulp plugin, gulp-server-livereload. Generally, the development process with

different build tools looks very similar nowadays: you set up the environment, find the plugins

you need, install and configure them - and violà!

I've chosen that server plugin because it comes with one handy feature: it automatically reloads the opened pages in your web-browser if any of the files you are browsing has changed. Here's the code of our serving task:

gulp.task('serve', function () {

gulp.src('public/')

.pipe(server({

livereload: true,

directoryListing: false,

open: true

}));

});But if you remember, we are compiling our sources from SCSS/Jade into the public/ directory.

So how the server would know if anything changed in our *.scss or *.jade files? We need to

reload the page in web-browser if anything changes in those files. To do that, we'll write one

more task, which will re-build our source files if anything changes:

gulp.task('watch', function () {

gulp.watch('src/**/*', [ 'build' ])

});Here we used two new features of Gulp: watching for file changes and running existing tasks from another task. Simple? Yeah, that simple! So we just tell Gulp: keep an eye on those files - if anything happens - run those tasks immediately! - and the magic happens.

But why should we run two tasks? Let's merge them into one so we just run gulp serve and get both live reload

and live re-compilation:

gulp.task('serve', function () {

gulp.watch('src/**/*', [ 'build' ])

gulp.src('public/')

.pipe(server({

port: 3000,

livereload: true,

directoryListing: false,

open: true

}));

});This task first defines a watcher for our sources and then starts server, which will react to any changes

in the public/ directory. To check how this awesomeness works, start gulp serve, open the

localhost:3000/test.html page and then change, for example,

color for the h1 tag to green. Save the SCSS file and just switch to the browser window, don't reload

it manually.