A semi-real-world problem

Let me introduce you functional programming with as few jargonisms and buzz-words as possible.

Shall we start with a simple problem to solve: get a random board game from top-10 games on BoardGamesGeek website and print out its rank and title.

BoardGameGeek website has an API: a request GET https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame will return an XML document like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<items termsofuse="https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi/termsofuse">

<item id="361545" rank="1">

<thumbnail value="https://cf.geekdo-images.com/lD8s_SQPObXTPevz-aAElA__thumb/img/YZG-deJK2vFm4NMOaniqZwwlaAE=/fit-in/200x150/filters:strip_icc()/pic6892102.png" />

<name value="Twilight Inscription" />

<yearpublished value="2022" />

</item>

<item id="276182" rank="2">

<thumbnail value="https://cf.geekdo-images.com/4q_5Ox7oYtK3Ma73iRtfAg__thumb/img/TU4UOoot_zqqUwCEmE_wFnLRRCY=/fit-in/200x150/filters:strip_icc()/pic4650725.jpg" />

<name value="Dead Reckoning" />

<yearpublished value="2022" />

</item>

</items>

In JavaScript a solution to this problem might look something like this:

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text())

.then(response => new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml"))

.then(doc => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name').getAttribute('value');

return { rank, name };

});

})

.then(games => {

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

})

.then(randomTop10Game => {

const log = `#${randomTop10Game.rank}: ${randomTop10Game.name}`;

console.log(log);

});

Quick and easy, quite easy to understand - seems good enough.

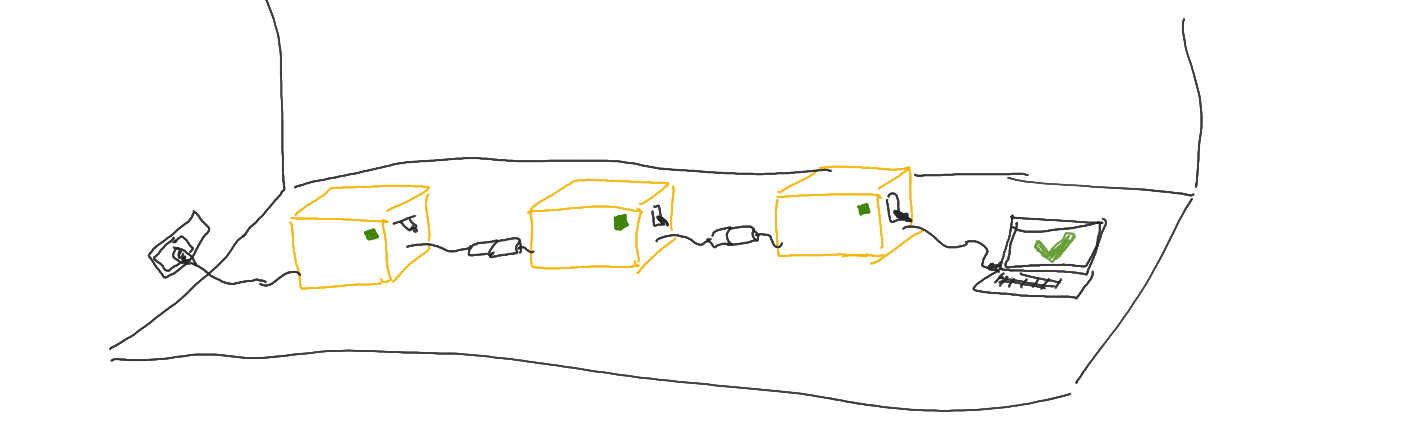

How about we write some tests for it? Oh, now it becomes a little bit clunky - we need to mock fetch call (Fetch API) and the Math.random. Oh, and the DOMParser with its querySelector and querySelectorAll calls too. Probably even console.log method as well. Okay, we will probably need to modify the original code to make testing easier (if even possible). How about we split the program into separate blocks of code?

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text());

const getResponseXML = (response) =>

new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

const extractGames = (doc) => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name').getAttribute('value');

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games) => {

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game) => {

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response => getResponseXML(response))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game));

Okay, now we can test some of the bits of the program without too much of a hassle - we could test that every call of getRandomGame returns a different value (which might not be true) but within the given list of values. We could test the extractGames function on a mock XML document and verify it extracts all the <item> nodes and its <name> child. Testing fetchAPIResponse and getResponseXML and printGame functions, though, would be a bit tricky without either mocking the fetch, console.log and DOMParser or actually calling those functions.

import {

fetchAPIResponse,

getResponseXML,

extractGames,

getRandomTop10Game,

printGame

} from "./index";

describe("fetchAPIResponse", () => {

describe("bad response", () => {

beforeEach(() => {

global.fetch = jest.fn(() => Promise.reject("404 Not Found"));

});

it("returns rejected promise", () => {

expect(fetchAPIResponse()).rejects.toBe("404 Not Found");

});

});

describe("ok response", () => {

beforeEach(() => {

global.fetch = jest.fn(() =>

Promise.resolve({

text() {

return `<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><items><item rank="1"><name value="Beyond the Sun"/></item></items>`;

}

})

);

});

it("returns rejected promise", () => {

expect(fetchAPIResponse()).resolves.toBe(

`<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><items><item rank="1"><name value="Beyond the Sun"/></item></items>`

);

});

});

});

describe("getResponseXML", () => {

describe("null passed", () => {

it("returns no <item> nodes", () => {

const doc = getResponseXML(null);

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll("item"));

expect(items).toHaveLength(0);

});

});

describe("invalid text passed", () => {

it("returns no <item> nodes", () => {

const doc = getResponseXML("404 not found");

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll("item"));

expect(items).toHaveLength(0);

});

});

describe("blank document passed", () => {

it("returns no <item> nodes", () => {

const doc = getResponseXML('<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>');

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll("item"));

expect(items).toHaveLength(0);

});

});

describe("valid document passed", () => {

it("returns <item> nodes", () => {

const doc = getResponseXML(

'<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><items><item rank="1"><name value="Beyond the Sun"/></item></items>'

);

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll("item"));

expect(items).toHaveLength(1);

});

});

});

describe("extractGames", () => {

describe("null document", () => {

it("throws an exception", () => {

expect(() => extractGames(null)).toThrow();

});

});

describe("empty document", () => {

it("returns empty array", () => {

const doc = new DOMParser().parseFromString("", "text/xml");

expect(extractGames(doc)).toStrictEqual([]);

});

});

describe("valid document", () => {

it("returns an array of games", () => {

const doc = new DOMParser().parseFromString(

`<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><items><item rank="3"><name value="Beyond the Sun"/></item></items>`,

"text/xml"

);

expect(extractGames(doc)).toStrictEqual([

{ name: "Beyond the Sun", rank: "3" }

]);

});

});

});

describe("getRandomTop10Game", () => {

describe("null passed", () => {

it("throws an exception", () => {

expect(() => getRandomTop10Game(null)).toThrow();

});

});

describe("empty array passed", () => {

it("returns undefined", () => {

expect(getRandomTop10Game([])).toStrictEqual(undefined);

});

});

describe("less than 10 element array passed", () => {

it("returns undefined", () => {

const games = [

{ name: "game1", rank: 1 },

{ name: "game2", rank: 2 }

];

const randomGames = [...new Array(100)].map(() =>

getRandomTop10Game(games)

);

expect(randomGames).toContain(undefined);

});

});

describe("10 or more element array passed", () => {

it("never returns undefined", () => {

const games = [

{ name: "game1", rank: 1 },

{ name: "game2", rank: 2 },

{ name: "game3", rank: 3 },

{ name: "game4", rank: 4 },

{ name: "game5", rank: 5 },

{ name: "game6", rank: 6 },

{ name: "game7", rank: 7 },

{ name: "game8", rank: 8 },

{ name: "game9", rank: 9 },

{ name: "game10", rank: 10 }

];

const randomGames = [...new Array(100)].map(() =>

getRandomTop10Game(games)

);

expect(randomGames).not.toContain(undefined);

});

it("returns an instance of each game", () => {

const games = [

{ name: "game1", rank: "1" },

{ name: "game2", rank: "2" },

{ name: "game3", rank: "3" },

{ name: "game4", rank: "4" },

{ name: "game5", rank: "5" },

{ name: "game6", rank: "6" },

{ name: "game7", rank: "7" },

{ name: "game8", rank: "8" },

{ name: "game9", rank: "9" },

{ name: "game10", rank: "10" }

];

const randomGames = [...new Array(100)].map(() =>

getRandomTop10Game(games)

);

expect(randomGames).toStrictEqual(expect.arrayContaining(games));

});

});

});

describe("printGame", () => {

describe("null passed", () => {

it("throws an exception", () => {

expect(() => printGame(null)).toThrow();

});

});

describe("game passed", () => {

const mockLogFn = jest.fn();

beforeEach(() => {

console.log = mockLogFn;

});

it("prints it to console", () => {

printGame({ name: "game 42", rank: "42" });

expect(mockLogFn).toHaveBeenCalledWith("#42: game 42");

});

});

});

In a lot of ways, I personally find these tests quite… hacky. But they seem to cover most of the functionality.

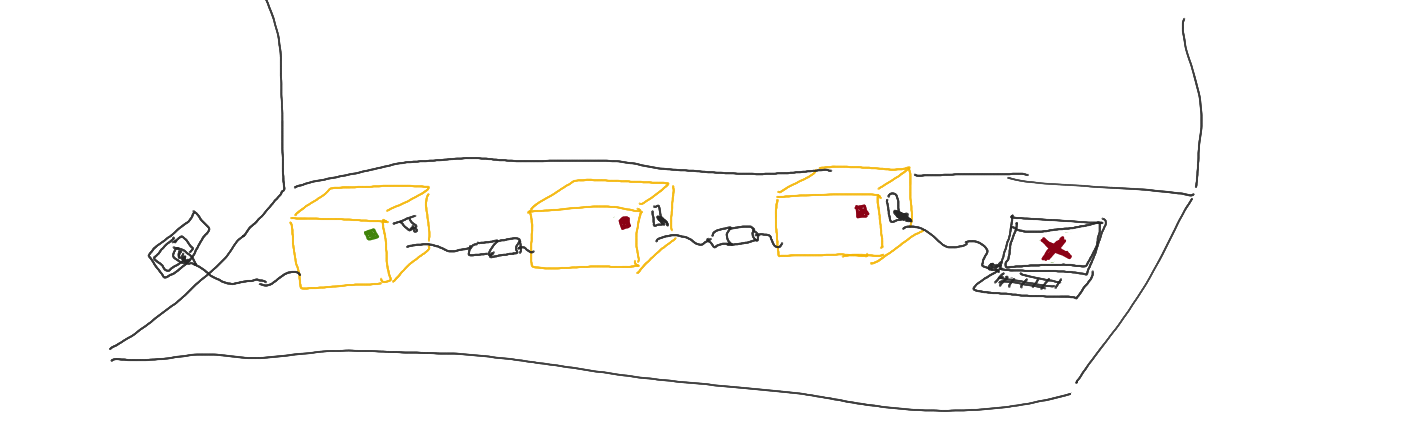

Let us talk about corner cases. As in, what would happen if the API does not return the result? Or what would happen if the result is not a valid XML (like 404 Not Found text)? Or what would happen if the XML is valid, but it does not contain any items or item[rank]>name[value] nodes? Or what if it only returns 5 results (or any number of results less than 10, for that matter)?

In most of the cases, the promise will get rejected (since an entire program is a chain of Promise.then calls). So you might think this is just fine and rely on the rejection logic handling (maybe even using Promise.catch).

If you want to be smart about these error cases, you would need to introduce the checks to each and every step of the chain.

In “classic” JS or TS you might want to return null (or, less likely, use Java-style approach, throwing an exception) when the error occurs.

This, however, comes with the need to introduce the null checks all over the place.

Consider this refactoring:

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text());

const getResponseXML = (response) => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

return null;

}

};

const extractGames = (doc) => {

if (!doc) {

return null;

}

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name').getAttribute('value');

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games) => {

if (!games) {

return null;

}

if (games.length < 10) {

return null;

}

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game) => {

if (!game) {

return null;

}

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response => getResponseXML(response))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game));

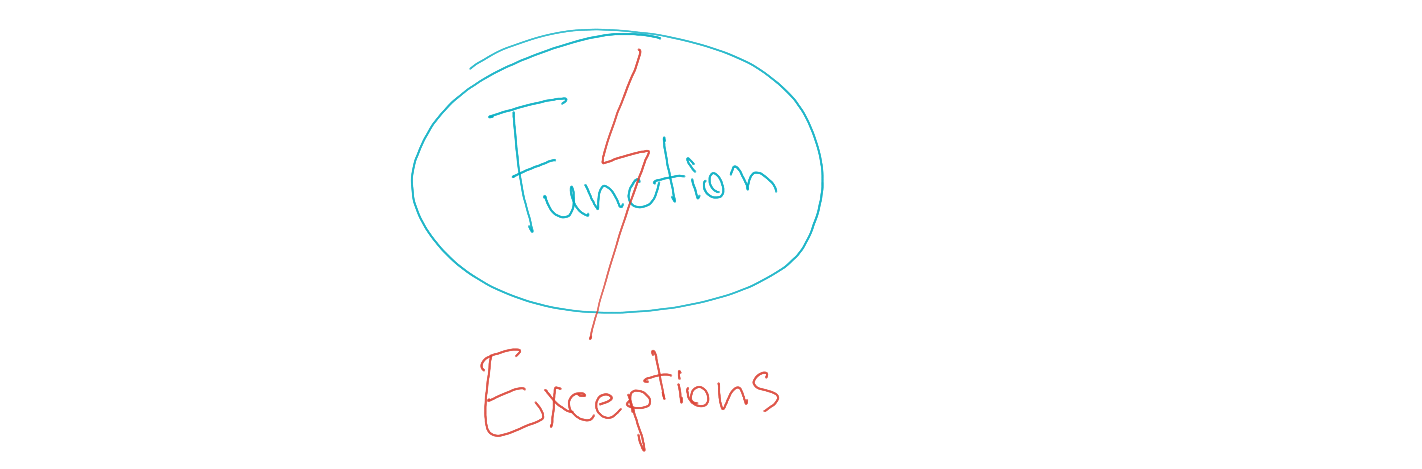

In case you don’t want to bother with null values or want to have a better logging (not necessarily error handling), you can straight away throw an exception:

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text());

const getResponseXML = (response) => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

throw 'Received invalid XML';

}

};

const extractGames = (doc) => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name').getAttribute('value');

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games) => {

if (!games) {

throw 'No games found';

}

if (games.length < 10) {

throw 'Less than 10 games received';

}

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game) => {

if (!game) {

throw 'No game provided';

}

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response => getResponseXML(response))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game))

.catch(error => console.error('Failed', error));

Alternatively, since an entire program is a chain of promises, you could just return a rejected promise:

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text());

const getResponseXML = (response) => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

return Promise.reject('Received invalid XML');

}

};

const extractGames = (doc) => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name').getAttribute('value');

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games) => {

if (!games) {

return Promise.reject('No games found');

}

if (games.length < 10) {

return Promise.reject('Less than 10 games received');

}

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game) => {

if (!game) {

return Promise.reject('No game provided');

}

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response => getResponseXML(response))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game))

.catch(error => console.error('Failed', error));

That’s all good and nice and we seem to have covered most of the edge case scenarios (at least those we could think of).

Now, what if I tell you the program is still not entirely correct? See those querySelector calls? They might return null if the node

or the attribute is not present. And we do not want those empty objects in our program’ output. This might be tricky to catch immediately

while developing the code.

One might even argue that most of those errors would have been caught by the compiler, if we have used something like TypeScript.

And they might be right - for the most part:

interface Game {

name: string;

rank: string;

}

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text());

const getResponseXML = (response: string) => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

throw 'Received invalid XML';

}

};

const extractGames = (doc: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank') ?? '';

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value') ?? '';

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game>) => {

if (!games) {

throw 'No games found';

}

if (games.length < 10) {

throw 'Less than 10 games received';

}

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game: Game) => {

if (!game) {

throw 'No game provided';

}

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(r => getResponseXML(r))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game))

.catch(error => console.error('Failed', error));

Not too many changes, but those pesky little errors were caught at development time, pretty much.

The testing is still a challenge, though.

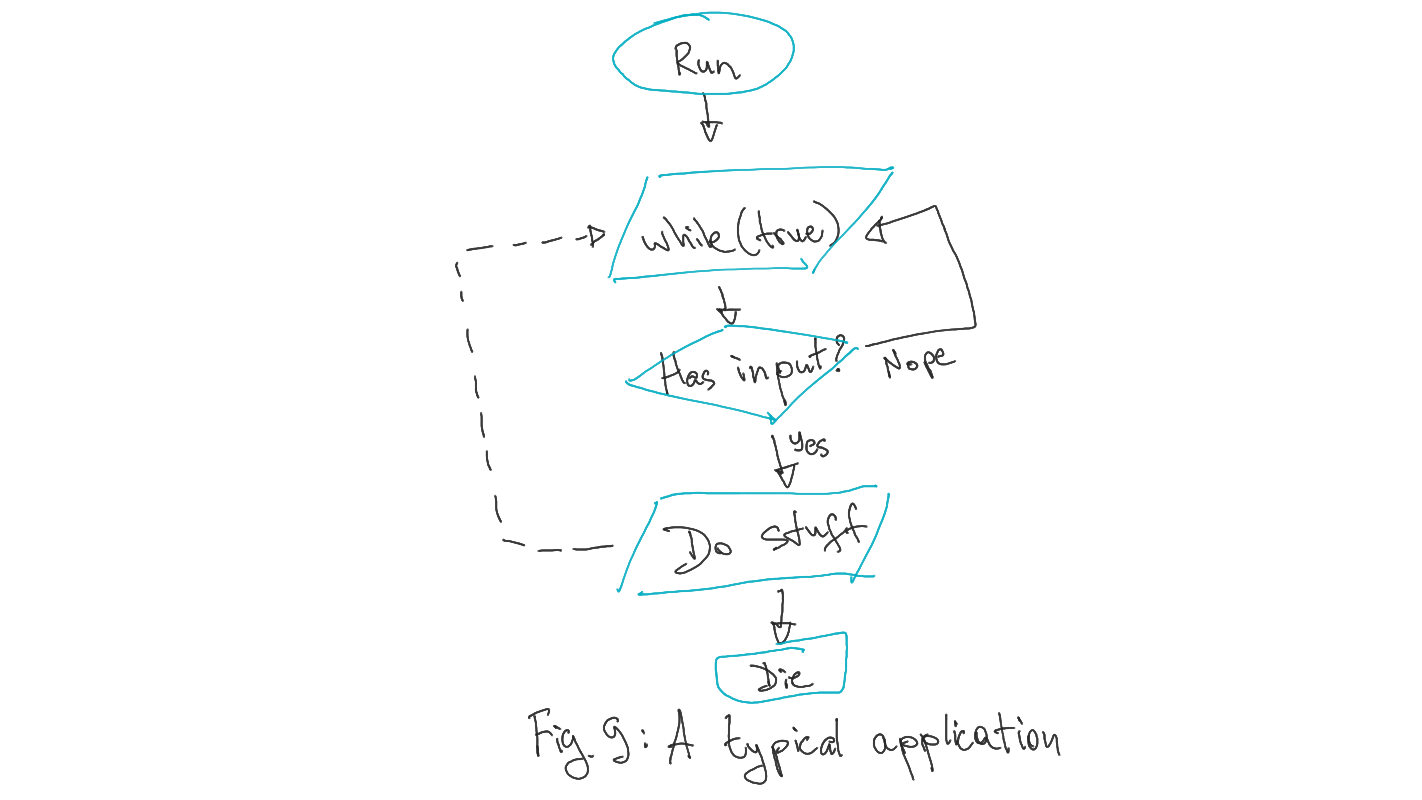

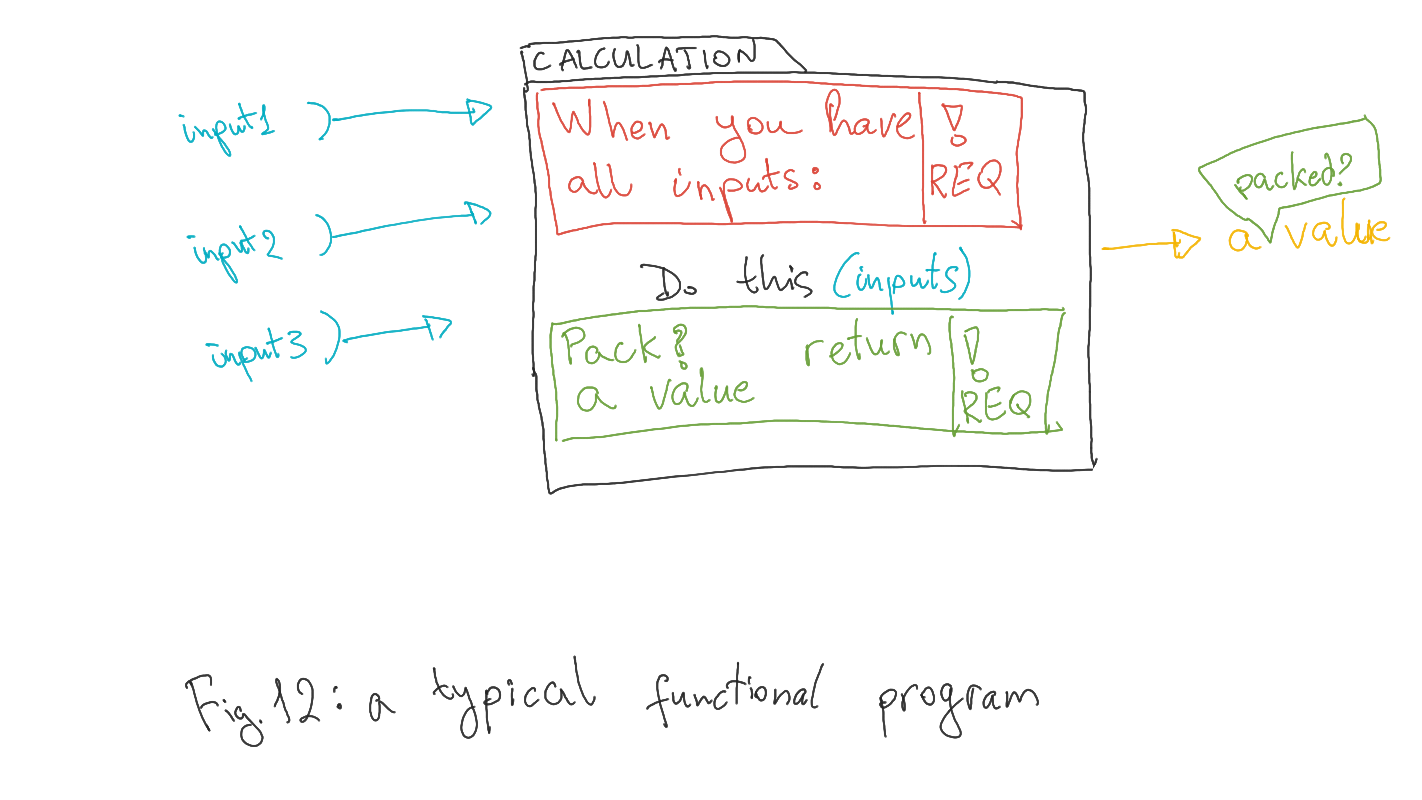

There is a application design approach which might be able to solve quite a bit of the aforementioned issues.

Let me introduce you to the world of functional programming without a ton of buzzwords and overwhelming terminology.

Disclaimer

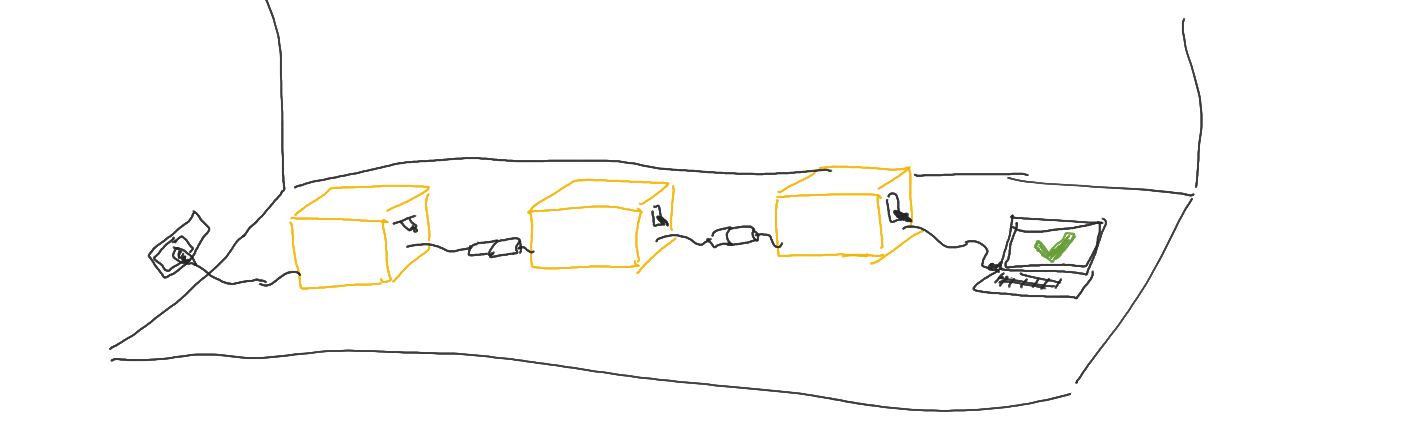

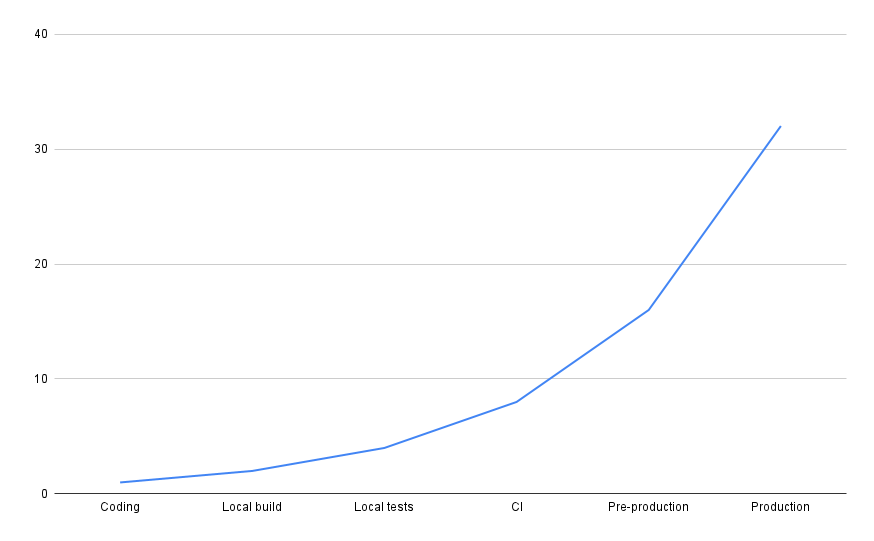

A big disclaimer before diving too deep: I am going to introduce all of the concepts without relying on any frameworks,

libraries, specific programming languages and whatnot - just sticking to the hand-written TypeScript. This might seem like

a lot of boilerplate and overhead for little benefit, but (with notes of a philosophy) the biggest benefit is in the cost of

detecting and fixing errors in the code:

- IDE highlighting an error (and maybe even suggesting a fix) - mere seconds of developer’s time

- Local build (compiling the code locally, before pushing the code to the repository) - minutes, maybe tens of minutes

- CI server build, running all the tests possible - around an hour

- Pre-production environment (manual testing on dedicated QA / staging environment or even testing on production) - around few hours, may involve other people

- Production - measured in days or months and risking the reputation with the customers

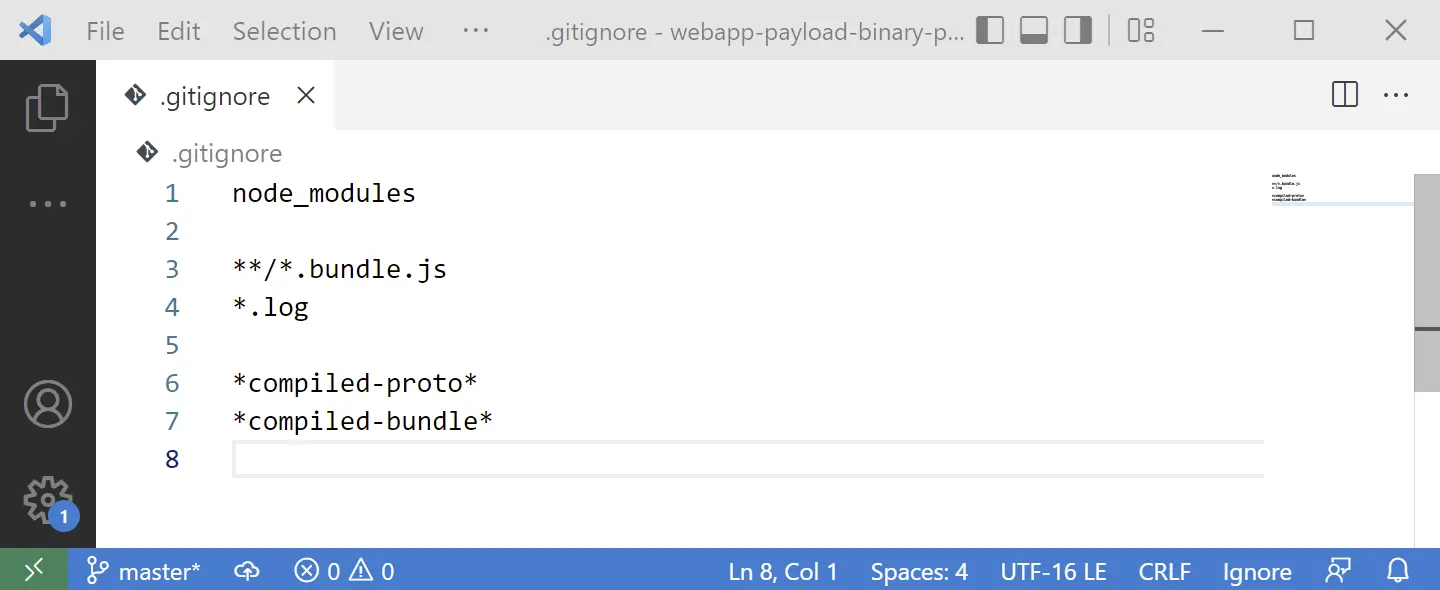

![]()

Hence if we could detect the errors while writing the code the first time - we could potentially save ourselves a fortune measured in both time and money.

Fancy-less introduction to functional programming

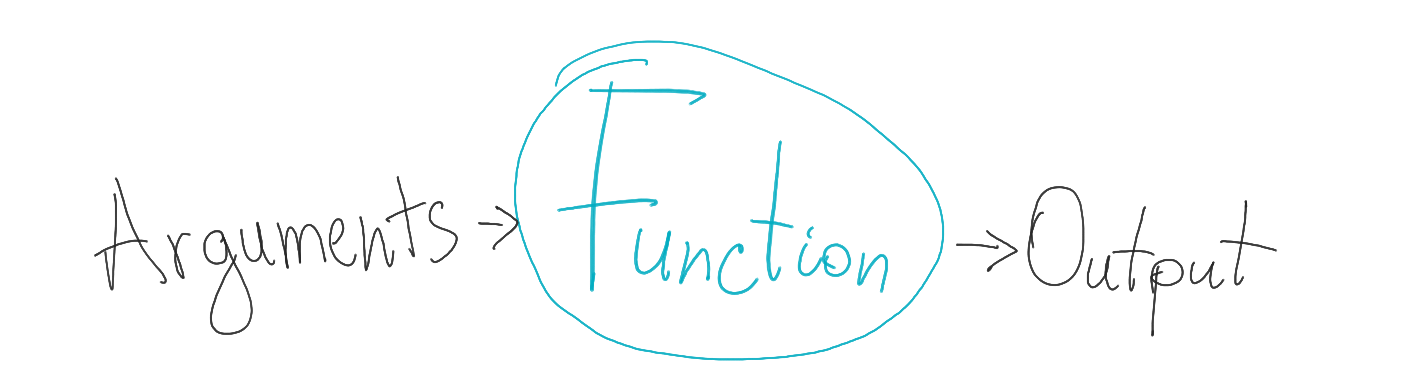

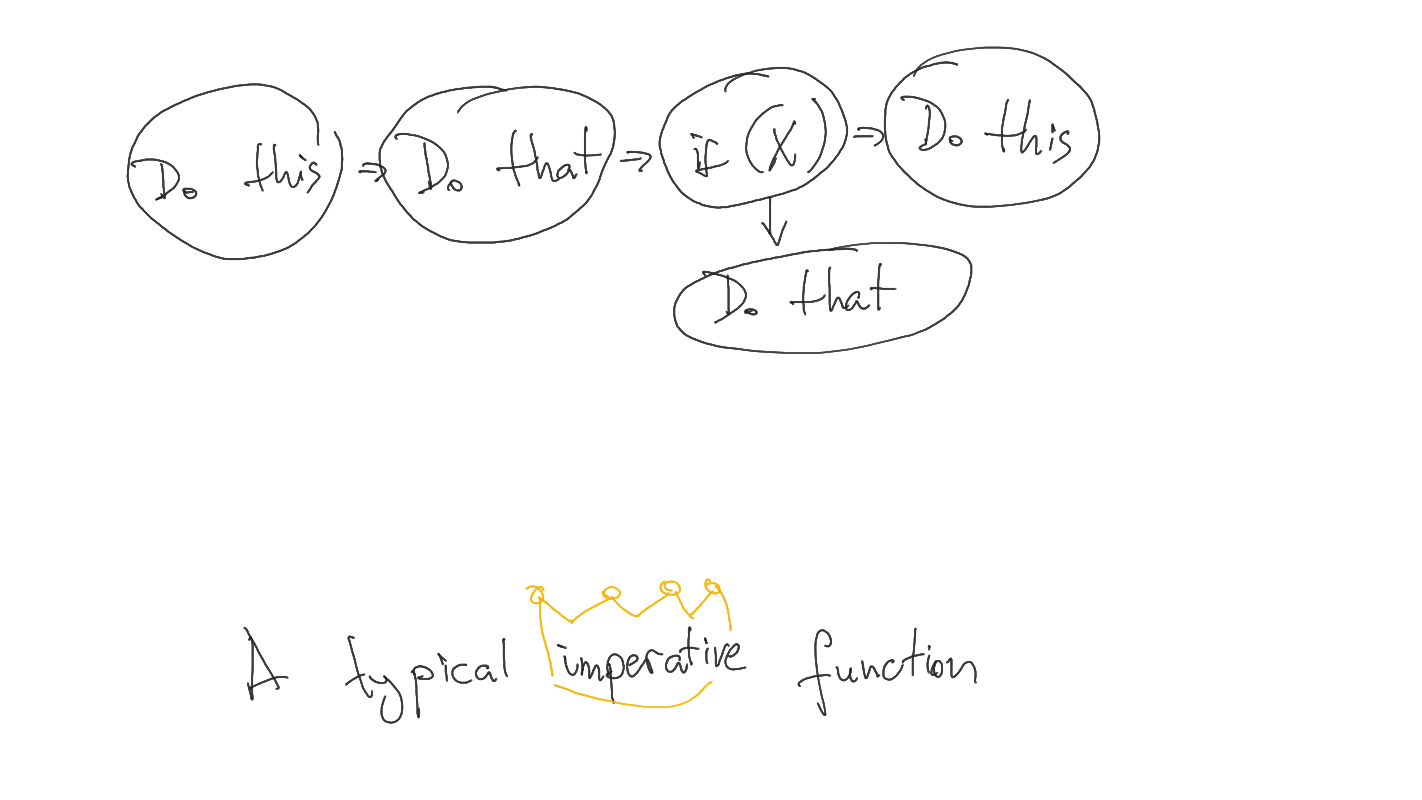

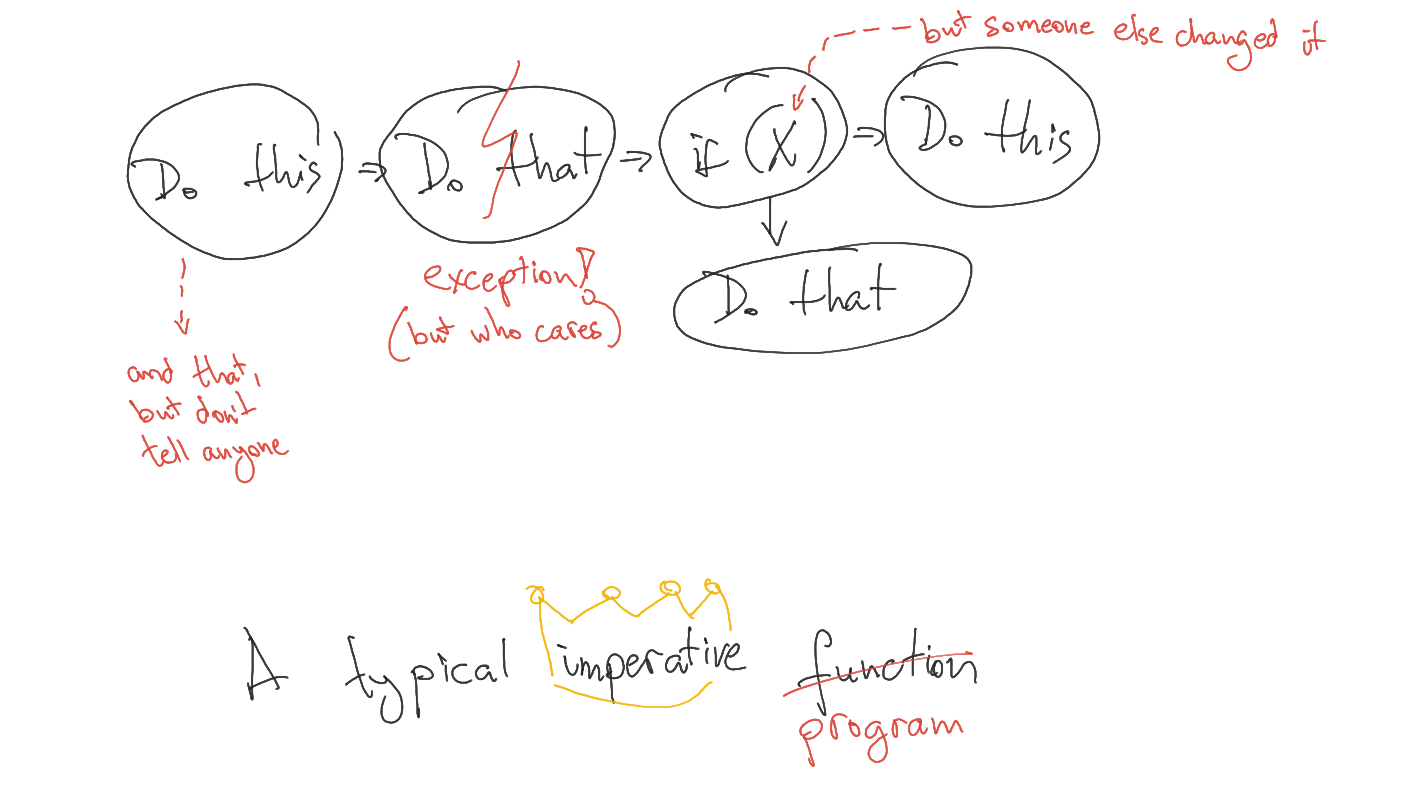

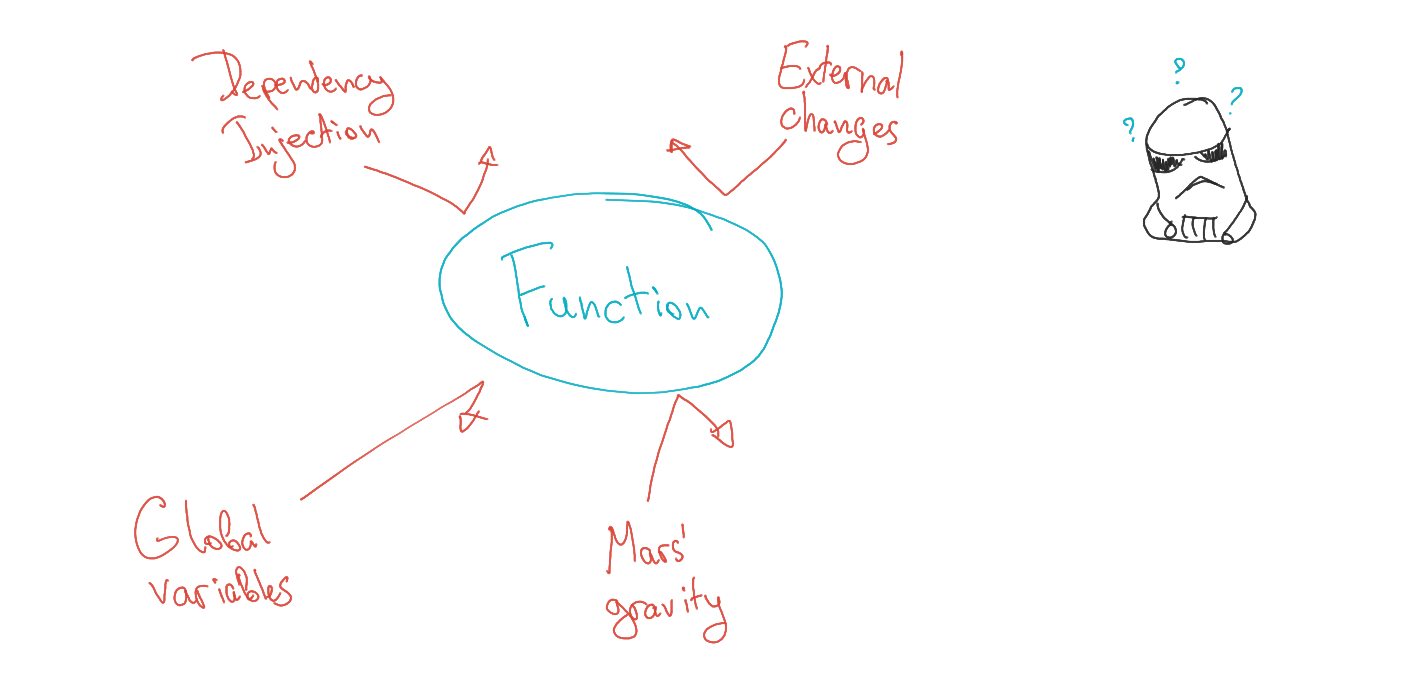

The ideas of functional programming are quite simple.

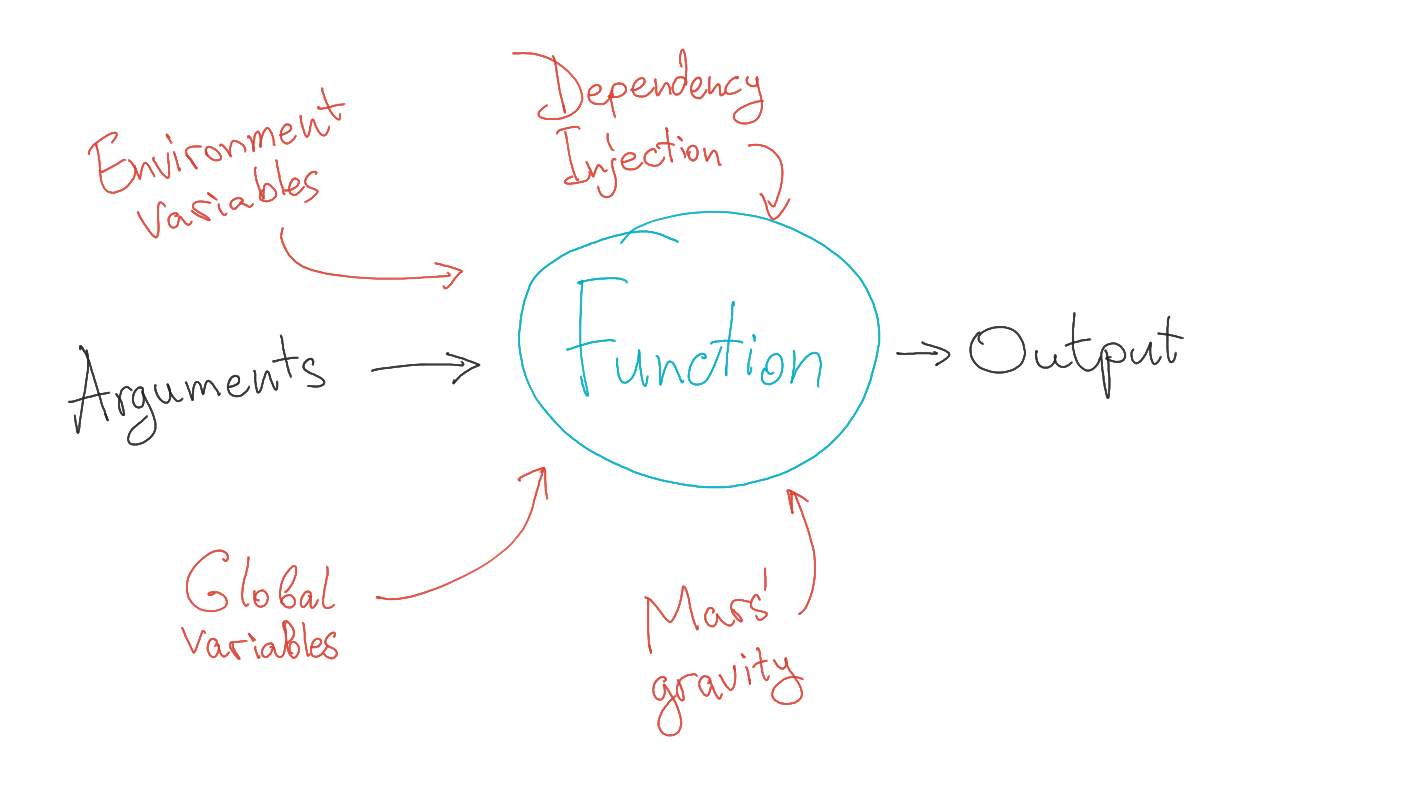

In functional programming the assumption is that every function only operates on the arguments

it has been passed and nothing else. It can not change the “outer world” - it can have values

temporarily assigned to internal constants, nothing more - take it as there are no variables.

A function should always return the same result for the same arguments, so functions are

always predictable, no matter how many times you call them.

That sounds good and nice, but how does that solve the issues of the above problem, you might ask.

For the most part the functions we have extracted already comply with the ideas of

functional programming - do they not?

Well, not really. For once, fetching the data from the API is a big questionmark on how it fits into the picture of functional programming. Leaving the fetching aside, we have a random call in the middle.

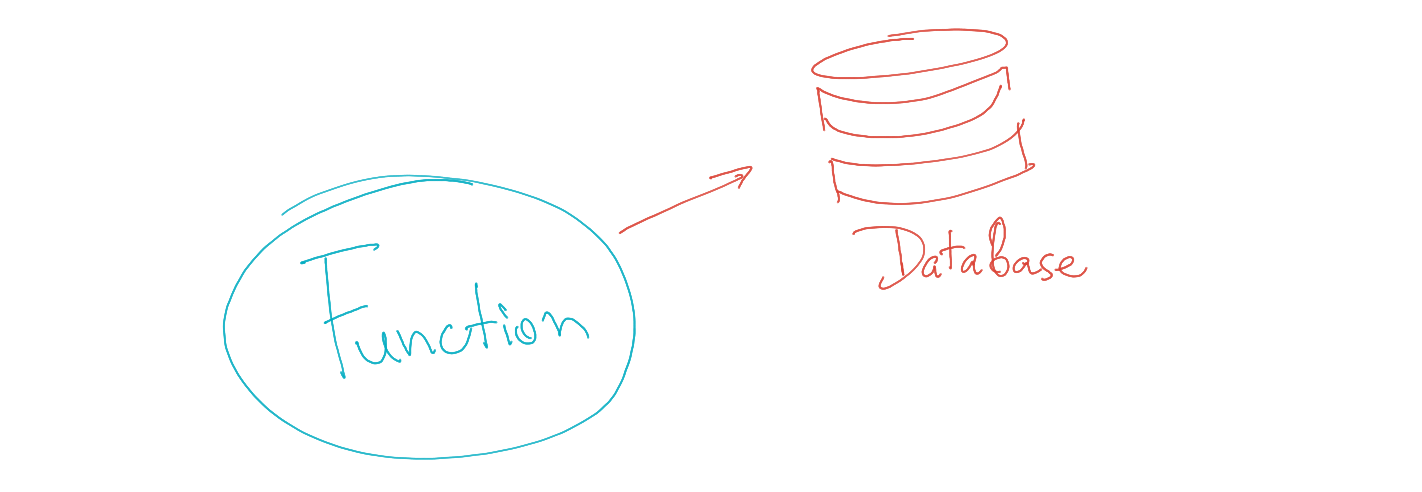

We also log some output to the console (and thus change the “outer world”, outside the printGame function).

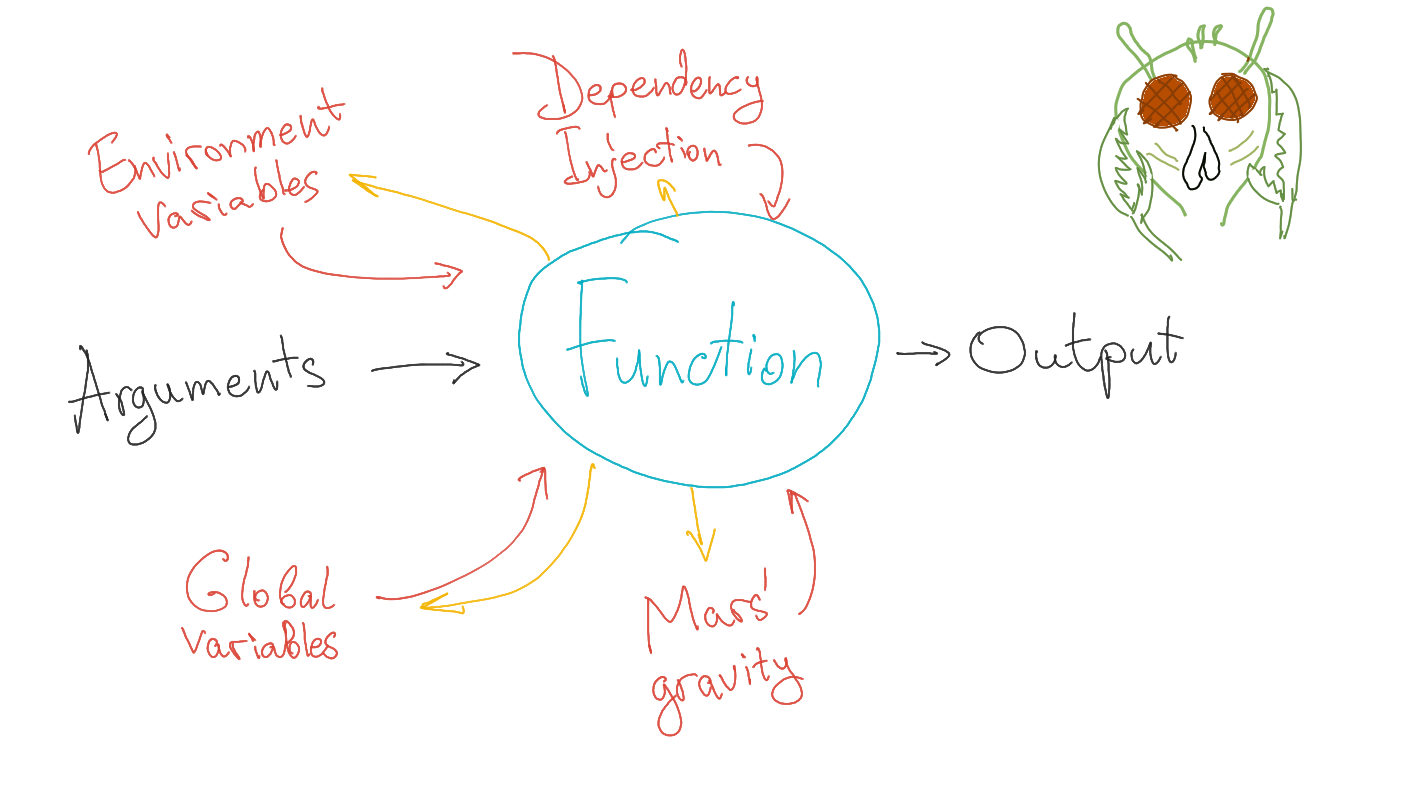

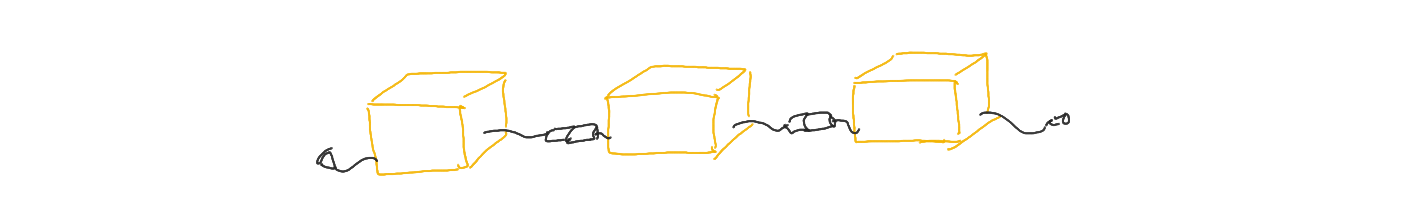

For a lot of things like those, functional programming tries to separate the “pure functional operations” and “impure operations”.

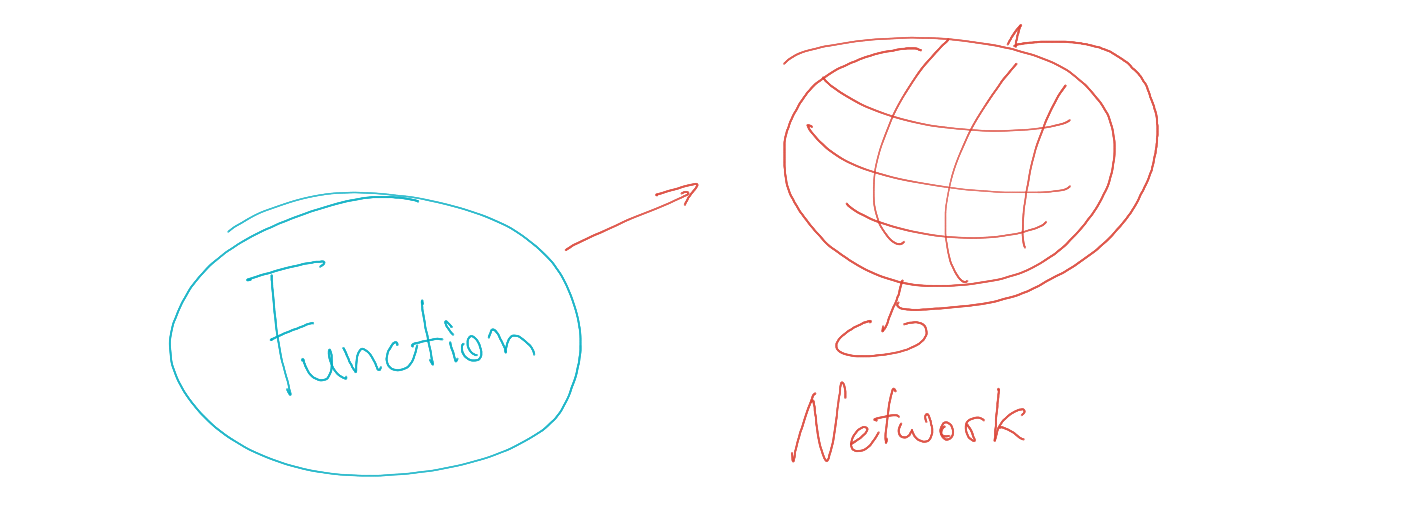

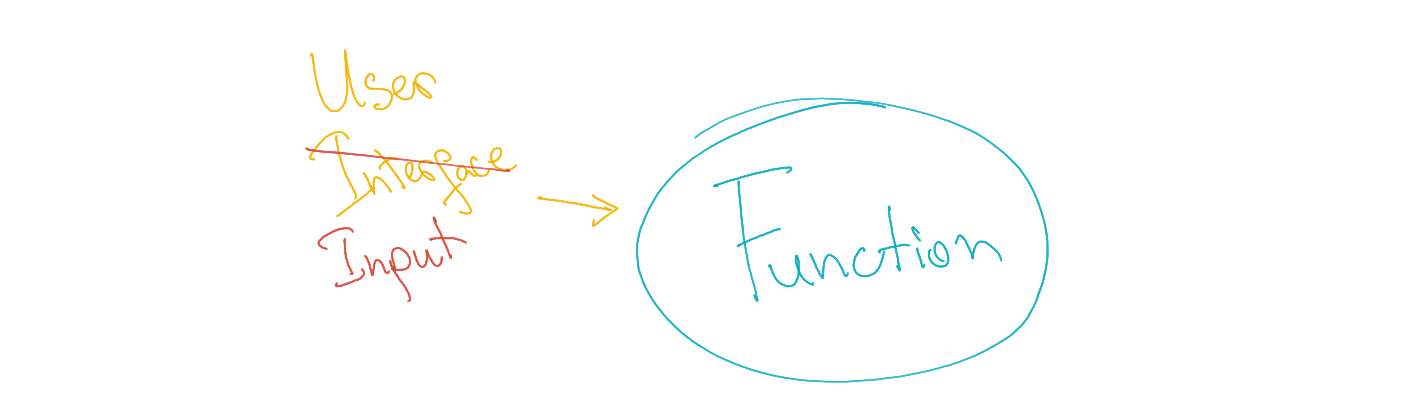

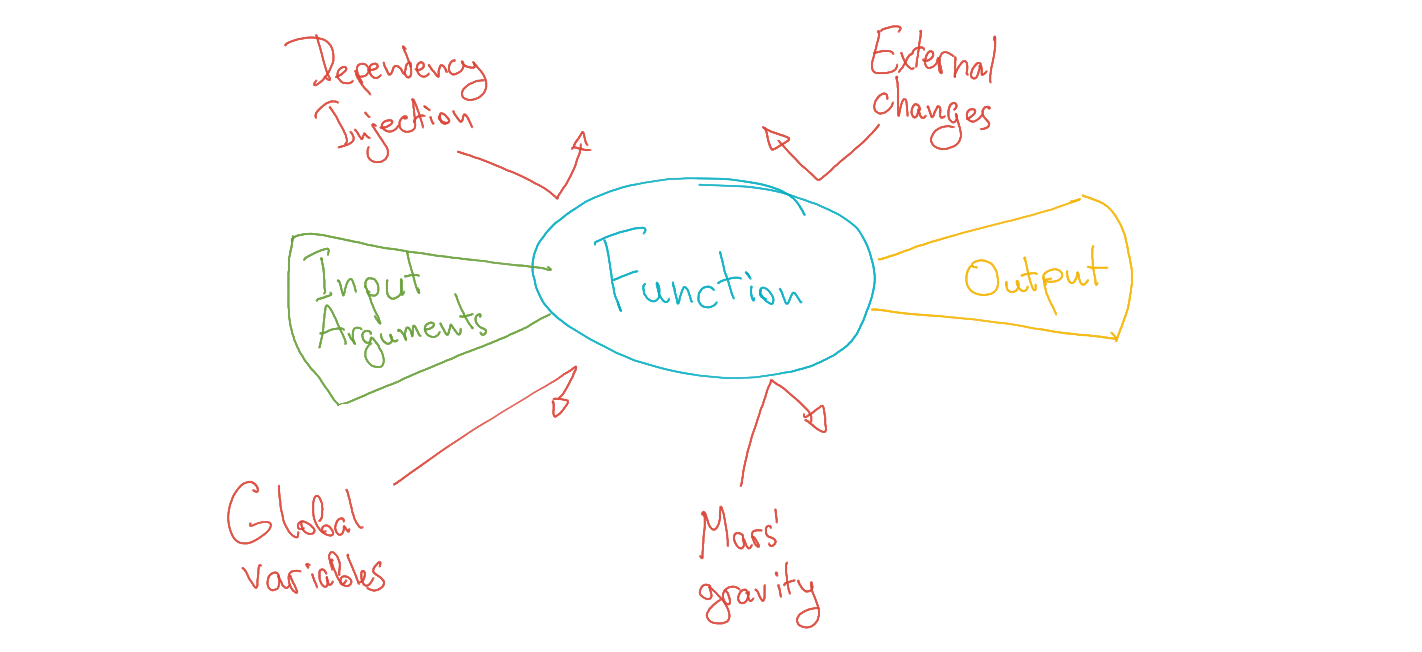

See, in functional programming you operate these “pure functions”, which only use constants and inputs to produce their outputs. So a program would be nothing but a chain of function calls. With “simple” functions, returning the values which the next function in the chain can take as an input argument, this is quite easy.

Take the code above as an example:

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response => getResponseXML(response))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game));

This could have been written as

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response =>

printGame(

getRandomTop10Game(

extractGames(

getResponseXML(response)

)

)

)

);

Since each next function in the chain accepts exactly the type the previous function has returned, they all combine quite well.

In other languages and some libraries there are operators to combine functions into one big function:

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response =>

_.flow([ getResponseXML, extractGames, getRandomTop10Game, printGame ])(response)

);

or

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(response ->

getResponseXML.andThen(extractGames).andThen(getRandomTop10Game).andThen(printGame).aplly(response)

);

You will understand why this matters in a minute.

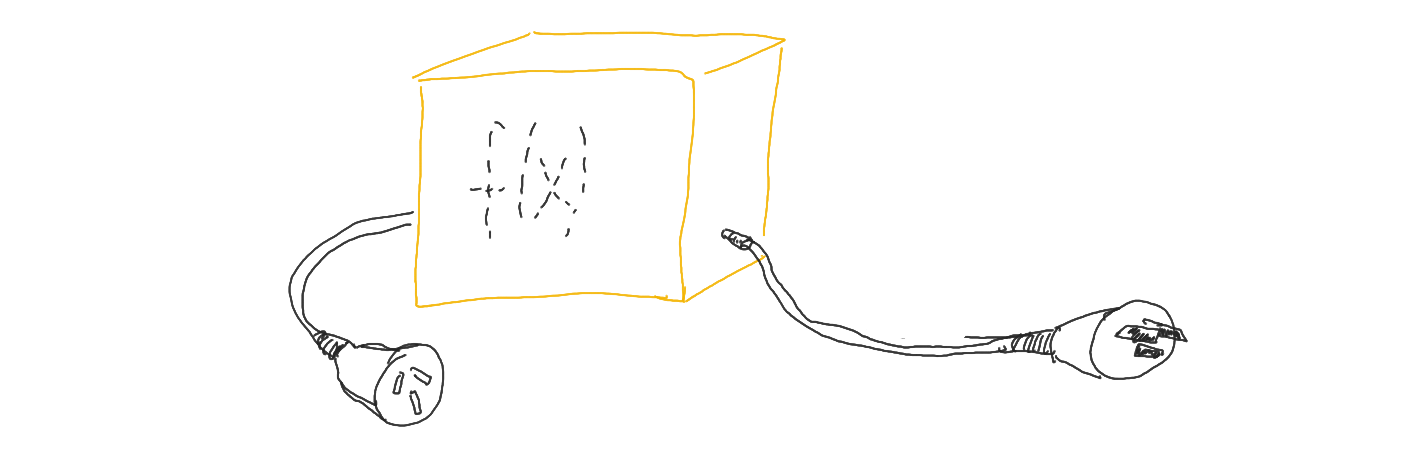

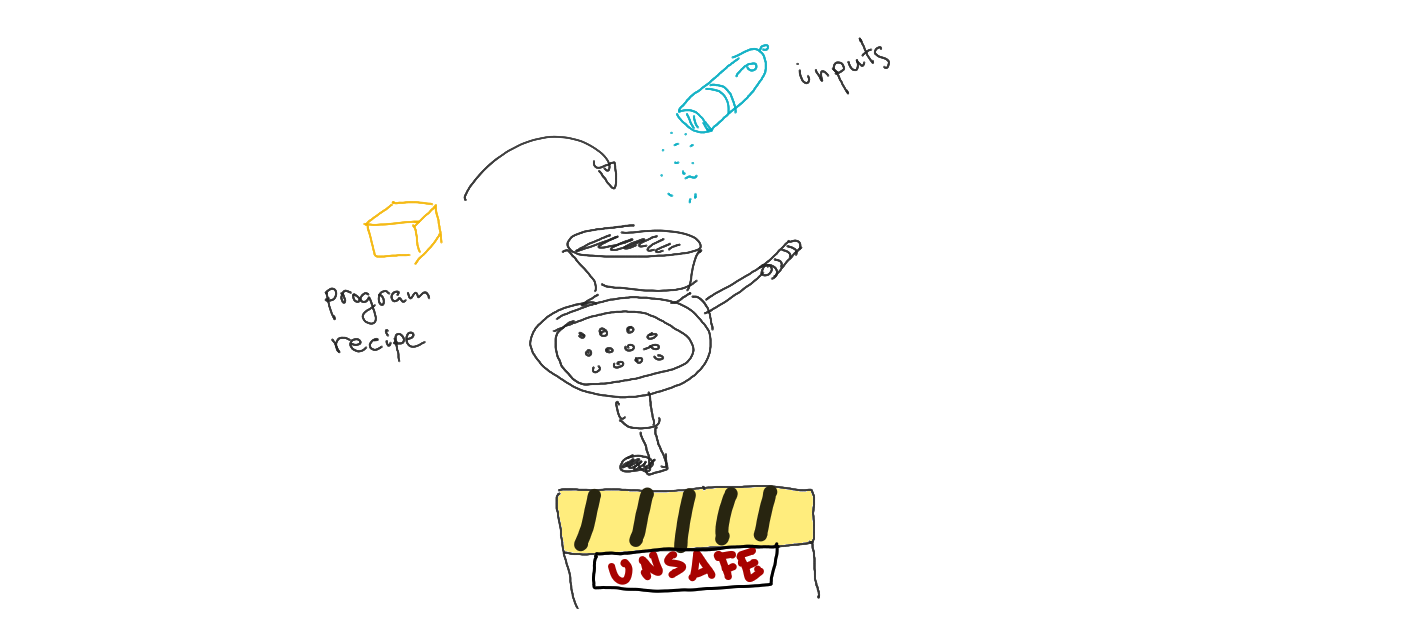

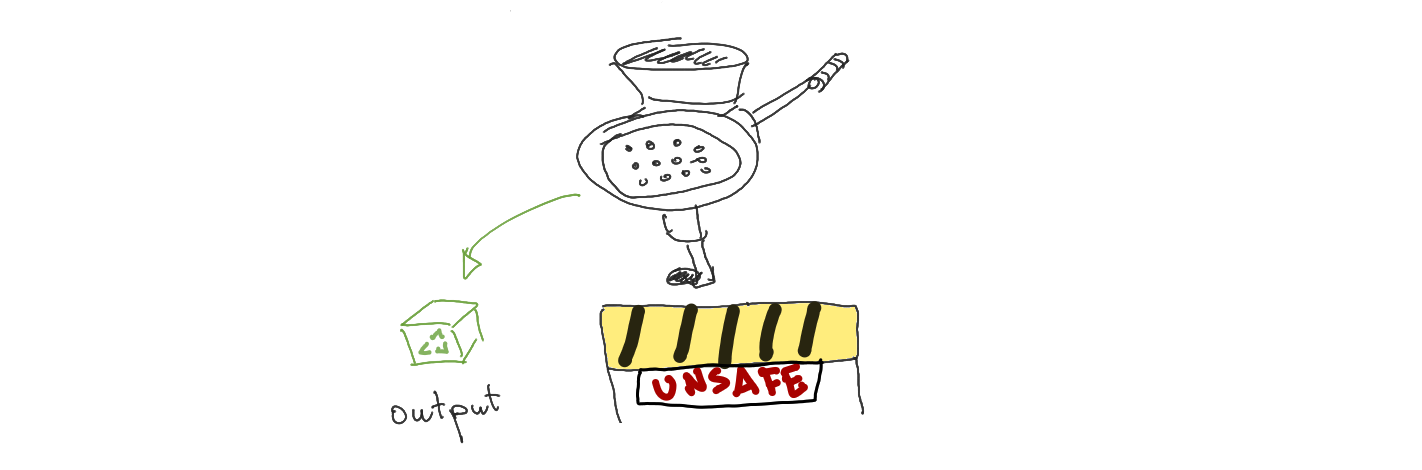

There are also functions which need to interact with the outer world. In that case, functional programming suggests that we wrap them in specific constructions and do not run them immediately.

Instead, we weave them into the program, describing what would happen to the result of the wrapped function call when we get one. This makes programs again, “pure functional”, “safe” (as in not operating outside of the boundaries of the program itself, all is contained in the function call chains). Then, once we run the program, we enter the world of “unsafe” and execute all those wrapped functions and run the rest of the code once we get the results in place.

Sounds a bit hard to comprehend.

Let me rephrase this with few bits of code.

For the problem above, we are trying to get the response of an API somewhere in the outer world.

This is said to be an “unsafe” operation, since the data lives outside of the program, so we need to wrap this operation in a “safe” manner. Essentially, we will create an object which describes an intention to run the fetch call and then write our program around this object to describe how this data will be processed down the line, when we actually run the program (and the fetch request together with it).

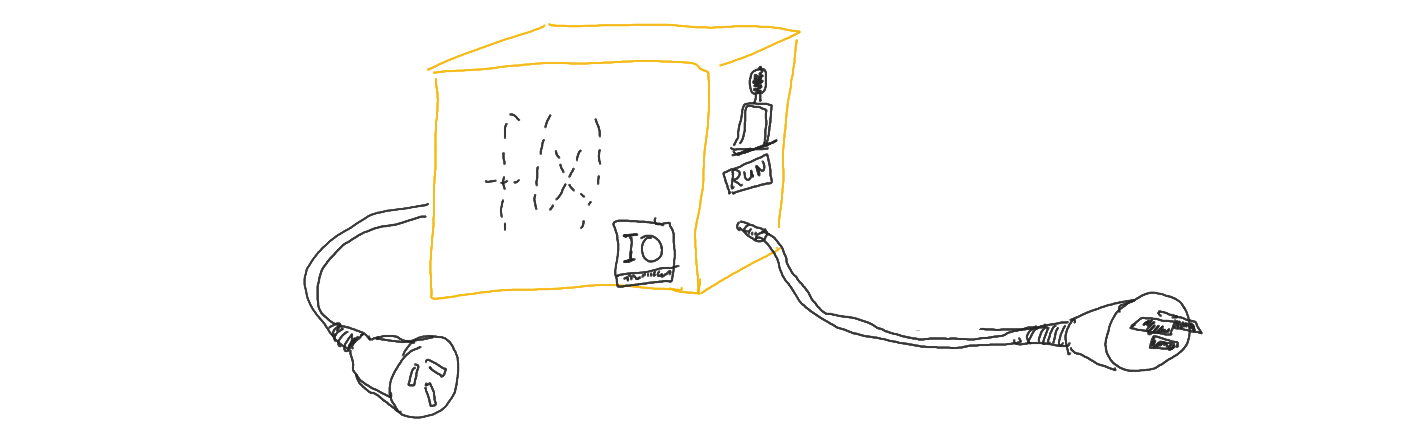

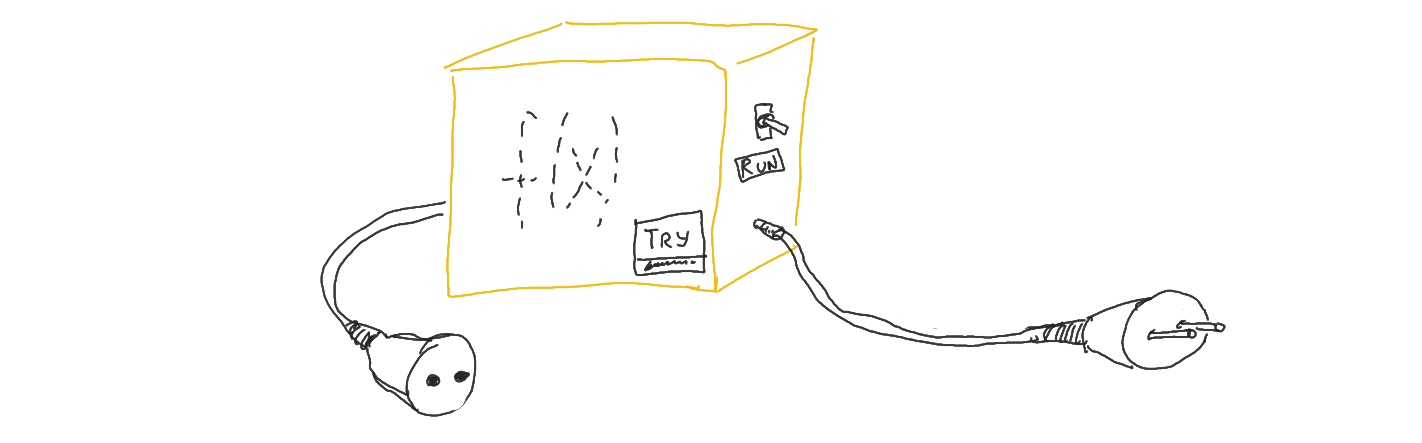

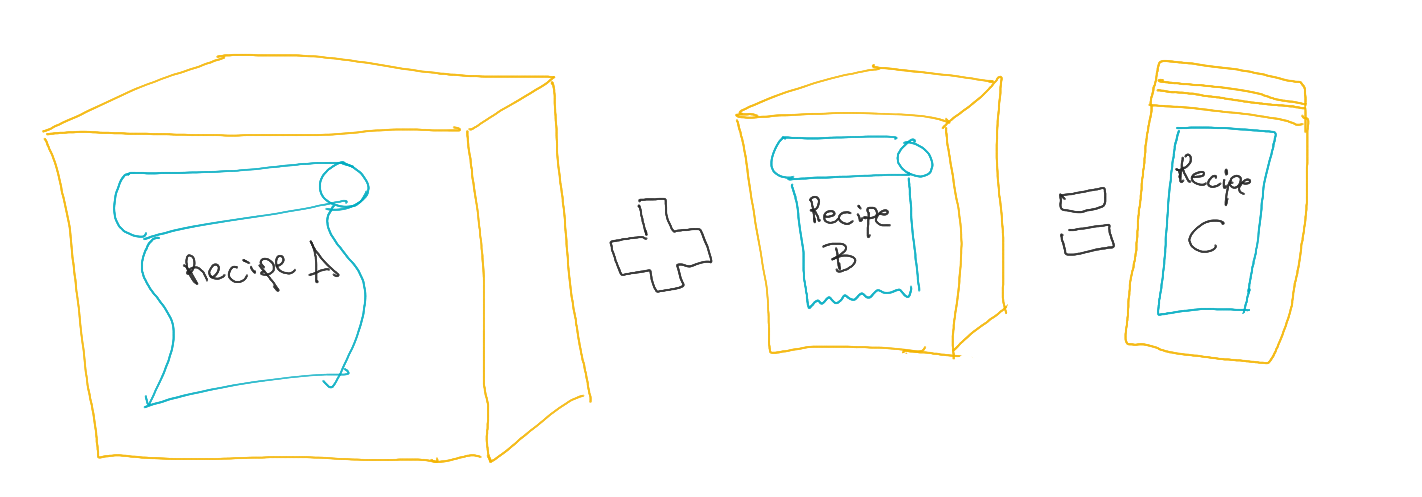

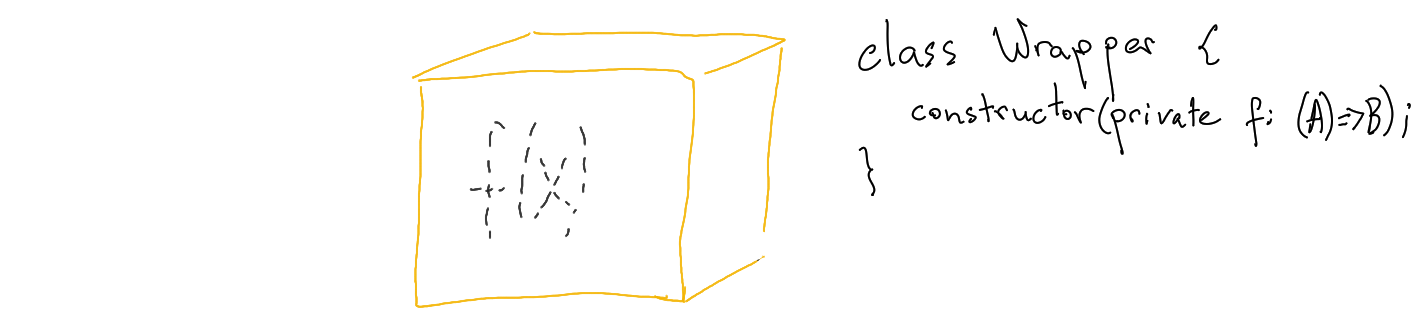

Let’s go through the thought process all together: we first need a class to wrap an unsafe function without executing it:

class IO {

constructor(private intentionFunc: Function;) {

}

}

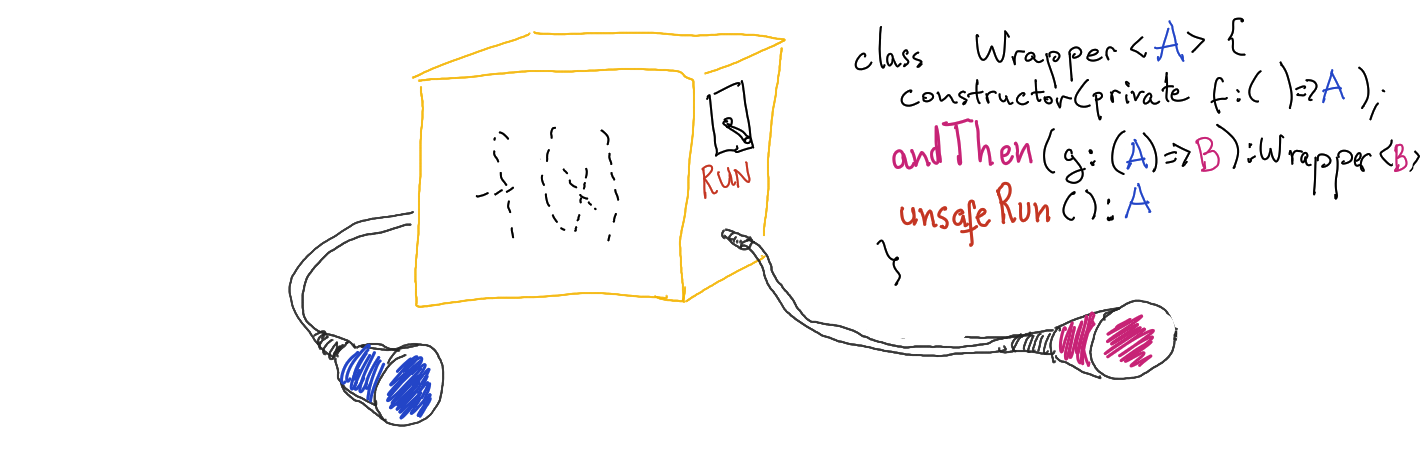

We then need a way to explicitly execute this function when we are ready to do so:

class IO {

constructor(private intentionFunc: Function;) {

}

unsafeRun() {

this.intentionFunc();

}

}

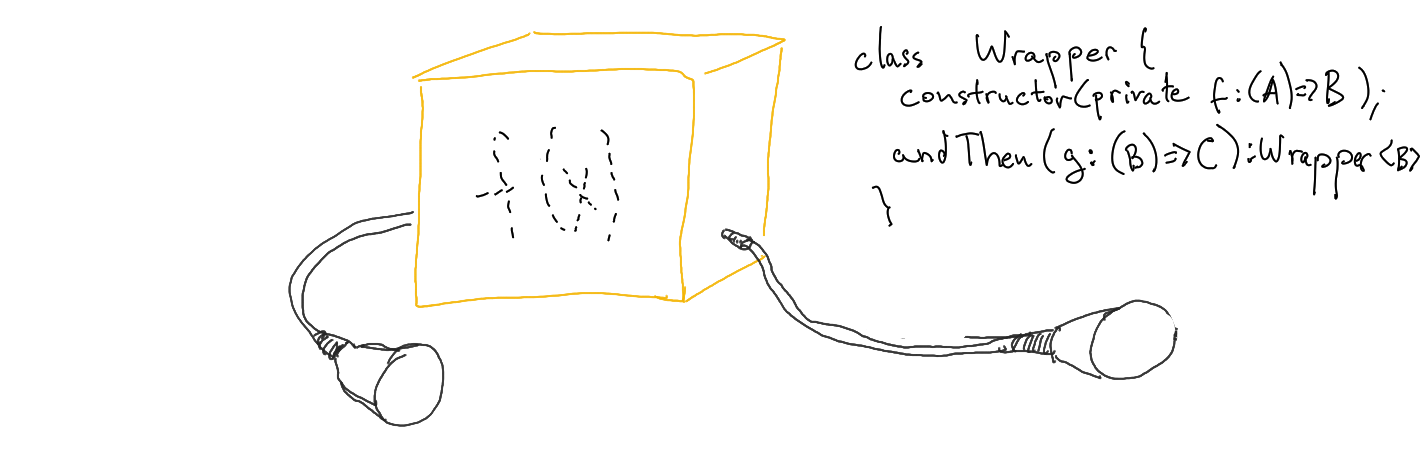

The last piece is we want to be able to chain this function with some other function in a safe manner (e.g. again, wrap the chained function):

class IO {

constructor(private intentionFunc: Function) {

}

andThen(func: Function) {

return new IO(() => func(this.intentionFunc()));

}

unsafeRun() {

this.intentionFunc();

}

}

Essentially, we save the function we intend to run in the intentionFunc member of an IO class.

When we want to describe what would happen to the result of the data, we return a new IO object with a new function - a combination of a function we will call around the call to the function we saved. This is important to understand why we return a new object: so that we do not mutate the original object.

You might see this new IO thing is very similar to the Promise available in JS runtime already.

The similarities are obvious: we also have this chaining with the then method. The call to the then method also returns a new object.

But the main issue with Promise is that they start running the code you passed in the constructor immediately. And that is exactly the issue we are trying to resolve.

Now, let us see how we would use this new IO class in the original problem:

new IO(() => fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`))

That would not work, however, since fetch call will return a Promise. So we need to somehow work with Promise instances instead.

Let me postpone this discussion for a short while.

We could have tried implementing an `unpromisify` helper which would make the `fetch` call synchronous, something like this:

const unpromisify = (promiseFn: Function) => {

const state = { isReady: false, result: undefined, error: undefined };

promiseFn()

.then((result) => {

state.result = result;

state.isReady = true;

})

.catch((error) => {

state.error = error;

state.isReady = true;

});

while (!state.isReady);

if (state.error) {

throw state.error;

}

return state.result;

};

But in JS world, promises start executing not immediately,

but once you leave the context of a currently running function. So having that endless while loop, waiting for a promise to get resolved has zero effect

since this loop will be running until the end of days, but unless you exit the function beforehand, the promise won’t start executing because JS is single threaded

and the execution queue / event loop prevents you from running the promise immediately.

For now, let us pretend this code would magically work, so we can talk about one important matter.

As I mentioned above, simple functions combine easily if one function accepts the same argument type the previous function returns.

Think extractGames and getRandomTop10Game - getRandomTop10Game accepts an argument of type Array<Game> while extractGames returns just that - Array<Game>.

But with this new construct of ours, IO, combining anything would be tricky:

type Func <A, B> = (_: A) => B;

class IO <A, B> {

constructor(private intentionFunc: Func<A, B>) {

}

andThen<C>(func: Func<B, C>) {

return new IO<A, C>((arg: A) => func(this.intentionFunc(arg)));

}

unsafeRun(arg: A) {

this.intentionFunc(arg);

}

}

interface Game {

name: string;

rank: string;

}

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

new IO(() => fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`).then(response => response.text()));

const getResponseXML = (response: string) => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

throw 'Received invalid XML';

}

};

const extractGames = (doc: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank') ?? '';

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value') ?? '';

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game>) => {

if (!games) {

throw 'No games found';

}

if (games.length < 10) {

throw 'Less than 10 games received';

}

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game: Game) => {

if (!game) {

throw 'No game provided';

}

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(r => getResponseXML(r))

.andThen(doc => extractGames(doc))

.andThen(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.andThen(game => printGame(game))

.unsafeRun(undefined);

Except for a tricky class declaration to support strong types by TypeScript, not much is different, huh?

The one big issue with almost any of the functions we have is that they not always produce results.

And that is an issue, since functional programming dictates a function must always produce one.

The way we deal with this situation in functional programming is by using few helper classes, which describe the presence or abscence of a result.

You might actually know them by heart: T? also known as T | null, T1 | T2 - TypeScript has it all:

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game> | undefiend): Game | undefined => {

return games?.[Math.random() * 100 % 10];

};

const printGame = (game: Game | undefined): void => {

console.log(`#${game?.rank ?? ''}: ${game?.name ?? ''}`);

};

Whereas with the former, optional values, you can do chaining to some extent, this becomes a burden with alternate types:

const createGame3 = (item: Element): Error | Game => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value');

if (name && rank)

return { name, rank } as Game;

return new Error('invalid response');

};

const getResponseXML3 = (response: string): Error | XMLDocument => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

return new Error('Received invalid XML');

}

};

const extractGames3 = (doc: Error | XMLDocument): Error | Array<Game> => {

if (doc instanceof Error)

return doc;

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

const games = [] as Array<Game>;

for (let item of items) {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank');

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value');

if (name && rank)

games.push({ rank, name } as Game);

else

return new Error('invalida data in XML');

}

return games;

};

const getRandomTop10Game3 = (games: Error | Array<Game>): Error | Game => {

if (games instanceof Error)

return games;

return games[Math.random() * 100 % 10];

};

const printGame3 = (game: Error | Game): void => {

if (game instanceof Error)

return;

console.log(`#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`);

};

Observe how all those instanceof checks and questionmarks and pipes infested the code.

Let us have more conscise wrappers, very similar to what other functional programming technologies have:

abstract class Maybe <A> {

abstract andThen <B>(func: Func<A, B>): Maybe<B>;

abstract andThenWrap <B>(func: Func<A, Maybe<B>>): Maybe<B>;

static option <A>(value: A | null | undefined): Maybe<A> {

return (!value) ? Maybe.none<A>() : Maybe.some<A>(value);

}

static some <A>(value: A): Some<A> {

return new Some<A>(value);

}

static none <A>(): None<A> {

return new None<A>();

}

}

class Some <A> extends Maybe <A> {

constructor(private readonly value: A) {

super();

}

override andThen <B>(func: Func<A, B>): Maybe<B> {

return new Some(func(this.value));

}

override andThenWrap <B>(func: Func<A, Maybe<B>>): Maybe<B> {

return func(this.value);

}

}

class None <A> extends Maybe <A> {

constructor() {

super();

}

override andThen <B>(_: Func<A, B>): Maybe<B> {

return new None<B>();

}

override andThenWrap <B>(_: Func<A, Maybe<B>>): Maybe<B> {

return new None<B>();

}

}

The simplest (yet not entirely helpful) way to handle exceptions in functional programming world would be using a wrapper like this:

abstract class Either <A, B> {

abstract andThen <C>(func: Func<B, C>): Either<A, C>;

abstract andThenWrap <C>(func: Func<B, Either<A, C>>): Either<A, C>;

static left <A, B>(value: A): Either<A, B> {

return new Left<A, B>(value);

}

static right <A, B>(value: B): Either<A, B> {

return new Right<A, B>(value);

}

}

class Left <A, B> extends Either <A, B> {

constructor(private readonly value: A) {

super();

}

override andThen <C>(_: Func<B, C>): Either<A, C> {

return new Left<A, C>(this.value);

}

override andThenWrap <C>(func: Func<B, Either<A, C>>): Either<A, C> {

return new Left<A, C>(this.value);

}

}

class Right <A, B> extends Either <A, B> {

constructor(private readonly value: B) {

super();

}

override andThen <C>(func: Func<B, C>): Either<A, C> {

return new Right(func(this.value));

}

override andThenWrap <C>(func: Func<B, Either<A, C>>): Either<A, C> {

return func(this.value);

}

}

This might not look as simplistic or clean when defined, but see how it changes the code:

const extractGames = (doc: Either<Error, XMLDocument>): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

return doc.andThen((d: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(d.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank') ?? '';

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value') ?? '';

return { rank, name };

});

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Either<Error, Array<Game>>): Either<Error, Game> => {

return games.andThen(gs => gs[Math.random() * 100 % 10]);

};

const printGame = (game: Either<Error, Game>): void => {

game.andThen(g => console.log(`#${g.rank}: ${g.name}`));

};

Now, there are two parts where we still have those ugly questionmarks:

const extractGames = (doc: Either<Error, XMLDocument>): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

return doc.andThen((d: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(d.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank') ?? '';

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value') ?? '';

return { rank, name };

});

});

};

Let’s see if we can utilize the new helper classes to beautify this:

const createGame = (item: Element): Maybe<Game> => {

const rank = Maybe.maybe(item.getAttribute('rank'));

const name = Maybe.maybe(item.querySelector('name')).andThen(name => name.getAttribute('value'));

return rank.andThenWrap(r =>

name.andThen(n => ({ name: n, rank: r } as Game))

);

};

Now the issue is: the createGame function takes an Element and returns a Maybe<Game>, but the extractGames function should return an Either<Error, Array<Game>>.

So we can’t just write something like this and expect it to work:

const extractGames = (doc: Either<Error, XMLDocument>): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

return doc.andThen((d: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(d.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => createGame(item));

});

};

There simply is no constructor to convert from Maybe<T> to Either<A, B> both technically, in the code, and logically - what would be the Left and what would be the Right then? One might argue, for None we could return Left<?> and for Some<A> we could return Right<A>. That would be the closest to truth, but we still need to come up with a type for Left.

This might actually be a good time to consider if these two types have something in common and, potentially, extract few interfaces.

abstract class Wrappable <A> {

abstract andThen <B>(func: Func<A, B>): Wrappable<B>;

abstract andThenWrap <B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): Wrappable<B>;

}

abstract class Maybe <A> extends Wrappable <A> {

abstract override andThen <B>(func: Func<A, B>): Maybe<B>;

abstract override andThenWrap <B>(func: Func<A, Maybe<B>>): Maybe<B>;

abstract toEither<B>(func: () => B): Either<B, A>;

static option <A>(value: A | null | undefined): Maybe<A> {

return (!value) ? Maybe.none<A>() : Maybe.some<A>(value);

}

static some <A>(value: A): Some<A> {

return new Some<A>(value);

}

static none <A>(): None<A> {

return new None<A>();

}

}

class Some <A> extends Maybe <A> {

constructor(private readonly value: A) {

super();

}

override andThen <B>(func: Func<A, B>): Maybe<B> {

return new Some(func(this.value));

}

override andThenWrap <B>(func: Func<A, Maybe<B>>): Maybe<B> {

return func(this.value);

}

override toEither<B>(_: () => B): Either<B, A> {

return Either.right<B, A>(this.value);

}

}

class None <A> extends Maybe <A> {

constructor() {

super();

}

override andThen <B>(_: Func<A, B>): Maybe<B> {

return new None<B>();

}

override andThenWrap <B>(_: Func<A, Maybe<B>>): Maybe<B> {

return new None<B>();

}

override toEither<B>(func: () => B): Either<B, A> {

return Either.left<B, A>(func());

}

}

abstract class Either <A, B> extends Wrappable<B> {

abstract override andThen <C>(func: Func<B, C>): Either<A, C>;

abstract override andThenWrap <C>(func: Func<B, Either<A, C>>): Either<A, C>;

abstract leftToMaybe(): Maybe<A>;

abstract rightToMaybe(): Maybe<B>;

static left <A, B>(value: A): Either<A, B> {

return new Left<A, B>(value);

}

static right <A, B>(value: B): Either<A, B> {

return new Right<A, B>(value);

}

}

class Left <A, B> extends Either <A, B> {

constructor(private readonly value: A) {

super();

}

override andThen <C>(_: Func<B, C>): Either<A, C> {

return new Left<A, C>(this.value);

}

override andThenWrap <C>(func: Func<B, Either<A, C>>): Either<A, C> {

return new Left<A, C>(this.value);

}

leftToMaybe(): Maybe<A> {

return Maybe.some(this.value);

}

rightToMaybe(): Maybe<B> {

return Maybe.none<B>();

}

}

class Right <A, B> extends Either <A, B> {

constructor(private readonly value: B) {

super();

}

override andThen <C>(func: Func<B, C>): Either<A, C> {

return new Right(func(this.value));

}

override andThenWrap <C>(func: Func<B, Either<A, C>>): Either<A, C> {

return func(this.value);

}

leftToMaybe(): Maybe<A> {

return Maybe.none<A>();

}

rightToMaybe(): Maybe<B> {

return Maybe.some(this.value);

}

}

const createGame = (item: Element): Maybe<Game> => {

const rank = Maybe.option(item.getAttribute('rank'));

const name = Maybe.option(item.querySelector('name')).andThen(name => name.getAttribute('value'));

return rank.andThenWrap(r =>

name.andThen(n => ({ name: n, rank: r } as Game))

);

};

const extractGames = (doc: Either<Error, XMLDocument>): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

return doc.andThenWrap((d: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(d.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => createGame(item).toEither(() => new Error('bad item')));

});

};

const extractGames = (doc: Either<Error, XMLDocument>): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

return doc.andThenWrap((d: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(d.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.reduce((accEither, item) =>

accEither.andThenWrap(acc =>

createGame(item)

.toEither(() => new Error('bad item'))

.andThen(game => [...acc, game])

),

Either.right<Error, Array<Game>>([])

);

});

};

const getResponseXML = (response: string): Either<Error, XMLDocument> => {

try {

return Either<Error, XMLDocument>.right(new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml"));

} catch {

return Either<Error, XMLDocument>.left('Received invalid XML');

}

};

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

new PromiseIO(() => fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`).then(response => response.text()));

const program = fetchAPIResponse()

.map(r => getResponseXML(r))

.map(doc => extractGames(doc))

.map(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.map(game => printGame(game))

.unsafeRun();

But we can do better than this: we can get rid of all those Either and Maybe in functions which do not throw an error:

const createGame = (item: Element): Maybe<Game> => {

const rank = Maybe.maybe(item.getAttribute('rank'));

const name = Maybe.maybe(item.querySelector('name')).map(name => name.getAttribute('value'));

return rank.flatMap(r =>

name.map(n => ({ name: n, rank: r } as Game))

);

};

const getResponseXML = (response: string): Either<Error, XMLDocument> => {

try {

return Either<Error, XMLDocument>.right(new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml"));

} catch {

return Either<Error, XMLDocument>.left('Received invalid XML');

}

};

const extractGames = (doc: XMLDocument): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.reduce((accEither, item) =>

accEither.flatMap(acc =>

createGame(item)

.toEither(() => new Error('bad item'))

.map(game => [...acc, game])

),

Either.right<Error, Array<Game>>([])

);

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game>): Either<Error, Game> => {

if (games.length < 10) {

return Either<Error, Game>.left(new Error('Not enough games'));

}

return Either<Error, Game>.right(games[Math.random() * 100 % 10]);

};

const printGame = (game: Game): void => {

console.log(`#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`);

};

Now if we try to compose the program, we would get quite a few “type mismatch” errors:

const program = fetchAPIResponse()

.map(r => getResponseXML(r))

.map(doc => extractGames(doc))

.map(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.map(game => printGame(game))

.unsafeRun();

yielding

Argument of type 'Either<Error, XMLDocument>' is not assignable to parameter of type 'XMLDocument'.

Type 'Either<Error, XMLDocument>' is missing the following properties from type 'XMLDocument': addEventListener, removeEventListener, URL, alinkColor, and 247 more.

Argument of type 'Either<Error, Game[]>' is not assignable to parameter of type 'Game[]'.

Type 'Either<Error, Game[]>' is missing the following properties from type 'Game[]': length, pop, push, concat, and 25 more.

Argument of type 'Either<Error, Game>' is not assignable to parameter of type 'Game'.

Type 'Either<Error, Game>' is missing the following properties from type 'Game': name, rank

Let us follow the types being passed around:

const program = fetchAPIResponse()

.map(r => getResponseXML(r))

.map(doc => extractGames(doc))

.map(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.map(game => printGame(game))

.unsafeRun();

The issues begin when we try to call map on PromiseIO<Either<Error, XMLDocument>>:

fetchAPIResponse().map(r => getResponseXML(r))

Let’s recall how the method map on PromiseIO<A> looks like:

class PromiseIO<A> {

map<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIO<B>;

}

So it expects a function which takes the type which PromiseIO wraps and returns a new type to be wrapped in PromiseIO.

But the type current PromiseIO wraps is Either<Error, XMLDocument>.

While the function we pass, extractGames looks like this:

const extractGames = (doc: XMLDocument): Either<Error, Array<Game>>;

See the issue?

We could have fixed it by adding few more nested functions, like this:

const program = fetchAPIResponse()

.map(r => getResponseXML(r))

.map(docE => docE.flatMap(doc => extractGames(doc)))

.map(gamesE => gamesE.flatMap(games => getRandomTop10Game(games)))

.map(gameE => gameE.map(game => printGame(game)))

.unsafeRun();

Or by changing the signature of the functions to take Either<Error, ?> instead.

But there is a more neat way to handle cases like this in functional programming.

Since the entire program is a chain of andThen and andThenWrap calls on different

Wrappable objects, we can create one which will wrap the try..catch expression.

Consider the code which might fail:

const getResponseXML = (response: string): XMLDocument =>

new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

This might not return what we need, according to the DOMParser documentation.

When the string passed to the parseFromString method is not a valid document, the object

returned would be a document with a single node - <parsererror>.

Normally, in JS or TS, we would either return an “invalid” value (think null or undefined) or throw an exception.

In functional programming we could get away with returning a Maybe or Either object.

However, let us consider throwing exception just to paint the bigger picture:

const getResponseXML = (response: string): XMLDocument => {

try {

const doc = new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

if (doc.querySelector('parsererror'))

throw new Error('Parser error');

return doc;

} catch (e) {

}

};

The above function, once called, will actually do some work. Luckily, in this specific case it won’t

do anything too “offensive” in terms of functional programming restrictions (like going to the database or making network calls).

But it will do something rather than just return a value.

Every time we call this function, the new DOMParser will be created and it will parse the string.

In functional programming world, as mentioned above, the program is just a chain of calls.

So the way to handle situations like this would be to somehow wrap the actual work and only

execute it upon request.

The best way we could wrap work is in a function which is yet to be called:

() => new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml")

We then should allow for this code to be worked around in a “callback” manner (as you might be familiar with the concept from

NodeJS and event handlers in browser JS) - the entire program should build upon a concept of “when the result of this execution becomes available”.

The way to do so is already described above in terms of Wrappable class with its andThen and andThenWrap methods:

new XWrappable(() => new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml"))

.andThen(document => doSomething(document))

Hence we could build a new Wrappable which would wrap both the logic in the try block and the logic in the catch block.

However, it should not call neither of those blocks of logic until explicitly requested - so we should add a new method to this

new wrappable - to call the logic and return a certain value.

class ExceptionW <A> implements Wrappable <A> {

constructor(private readonly task: Func0<Wrappable<A>>, private readonly exceptionHandler: Func<unknown, Wrappable<A>>) {}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): ExceptionW<B> {

return new ExceptionW<B>(

() => this.runExceptionW().andThen(func),

(e) => this.runExceptionW(e).andThen(func)

);

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, ExceptionW<B>>): ExceptionW<B> {

return new ExceptionW<B>(

() => this.runExceptionW().andThenWrap(func),

(e) => this.runExceptionW(e).andThenWrap(func)

);

}

runExceptionW(): Wrappable<A> {

try {

return this.task();

} catch (e) {

return this.exceptionHandler(e);

}

}

}

Now the program from the beginning of the article can be re-written as follows:

const getResponseXML = (response: string): ExceptionW<XMLDocument> =>

new ExceptionW(

() => {

const doc = new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

if (doc.querySelector('parsererror'))

return Either<Error, XMLDocument>.left(new Error('Parser error'));

return Either<Error, XMLDocument>.right(doc);

},

(e) => Either<Error, XMLDocument>.left(e)

);

Just to confirm once more if you are still asking “why bother with this ExceptionW thing? why not to use Either right away?”:

this whole ExceptionW thing allows us to postpone running the actual logic and build the entire program as a function of

the result of this logic. In turn, when we are ready to execute the entire program, we can run this wrapped logic.

Let us see how this new function can be used in the program:

const program = (getResponseXML('invalid XML')

.andThenWrap(doc => extractGames(doc))

.andThenWrap(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.runExceptionW() as Either<Error, XMLDocument>>)

.andThen(result => console.log('success', result));

There is a little bit of a quirk around type casting ((???.runExceptionW() as Either<Error, XMLDocument>).andThen).

We can solve it by slightly modifying the runExceptionW method:

runExceptionW<W extends Wrappable<A>>(): W {

try {

return this.task() as W;

} catch (e) {

return this.exceptionHandler(e) as W;

}

}

With that, the code becomes a little bit cleaner:

const program = getResponseXML('invalid XML')

.andThenWrap(doc => extractGames(doc))

.andThenWrap(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.runExceptionW<Either<Error, XMLDocument>>()

.andThen(result => console.log('success', result));

With this new concept of wrapping an entire blocks of functionality in a Wrappable, we can solve a similar problem

with the initial program: promises.

Instead of just creating a promise object together with the Wrappable, we can instead hide it in a function.

Let us do this step by step. First, the interface implementation and the overall skeleton of a new class:

class PromiseIO <A> implements Wrappable<A> {

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIO<B> {

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, PromiseIO<B>>): PromiseIO<B> {

}

}

Now, to wrap the promise:

class PromiseIO <A> implements Wrappable<A> {

constructor(private readonly task: Func0<Promise<A>>) {}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIO<B> {

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, PromiseIO<B>>): PromiseIO<B> {

}

}

And running the wrapped promise:

class PromiseIO <A> implements Wrappable<A> {

constructor(private readonly task: Func0<Promise<A>>) {}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIO<B> {

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, PromiseIO<B>>): PromiseIO<B> {

}

unsafeRun(): Promise<A> {

return this.task();

}

}

Note how I explicitly called it “unsafe” - since promise can (and, most likely, will) work with an outside world,

we should only run it when we are ready to run the whole program, so it immediately produces the result as

a function of whatever the wrapped promise has returned.

Then, when we need to chain the logic off that promise, we do not really need to call the promise - instead,

we create a new Wrappable instance which will call the promise somewhere in the future.

So instead of calling wrappedPromise.then(func), which is now wrapped in a function () => Promise<A>,

we create a new PromiseIO wrappable with a new function, which will do something when the promise returns.

This is better explained with the code, in my opinion:

class PromiseIO <A> implements Wrappable<A> {

constructor(private readonly task: Func0<Promise<A>>) {

}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIO<B> {

return new PromiseIO<B>(() => this.unsafeRun().then(func));

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, PromiseIO<B>>): PromiseIO<B> {

return new PromiseIO<B>(() => this.unsafeRun().then(func));

}

unsafeRun(): Promise<A> {

return this.task();

}

}

Unfortunately, this won’t work. The issue is in the andThenWrap method.

Recall the interface of Wrappable<A>:

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): Wrappable<B>;

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): Wrappable<B>;

Now the code we have in there right now will work if the function func returned B,

which would be exactly what andThen method does:

this.unsafeRun().then(func)

new PromiseIO(() => this.unsafeRun().then(func))

But since the function func returns PromiseIO<B> instead, the result would be slightly different:

this.unsafeRun().then(func)

new PromiseIO(() => this.unsafeRun().then(func))

But notice how this is a nested PromiseIO object - can we maybe “unwrap” and “repack” it?

Turns out, we can - remember how a Promise<A>.then(() => Promise<B>) resolves in Promise<B>.

We can utilize this property of Promise, if the function we wrap will return Promise<Promise<B>>.

And that’s where our unsafeRun method can be utilized within the function we wrap:

new PromiseIO<B>(

() => {

const p1 = new PromiseIO<PromiseIO<B>>(

() => this.unsafeRun()

.then(func)

);

const p2: Promise<PromiseIO<B>> = p1.unsafeRun();

const p3: Promise<B> = p2.then(

(p: PromiseIO<B>) => p.unsafeRun()

);

return p3;

}

)

and then

class PromiseIO <A> implements Wrappable<A> {

constructor(private readonly task: Func0<Promise<A>>) {

}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIO<B> {

return new PromiseIO<B>(() => this.unsafeRun().then(func));

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, PromiseIO<B>>): PromiseIO<B> {

return new PromiseIO<B>(() =>

new PromiseIO<PromiseIO<B>>(() =>

this.unsafeRun()

.then(func)

)

.unsafeRun()

.then(p => p.unsafeRun())

);

}

unsafeRun(): Promise<A> {

return this.task();

}

}

Now let us build our solution again, using this newly acquired wrappable:

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

new PromiseIO(() => fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`).then(response => response.text()));

const program = fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response))

.andThen(doc => extractGames(doc))

.andThen(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.runExceptionW<Either<Error, XMLDocument>>()

.andThen(game => printGame(game))

.unsafeRun();

Uh-oh, there is an issue with the types again:

fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response))

.andThen(doc => extractGames(doc))

So we can not really use the existing functions directly - the types mismatch.

The issue is that they are nested twice already - PromiseIO<ExceptionW<XMLDocument>>.

And the extractGames function expects just the XMLDocument as an input.

Is there a way to extract the double-wrapped value?

Well, in functional programming, we use another wrappable (oh really) which ignores the outside

wrappable and operates on the nested one. We call them “transformers”:

new PromiseIOT(fetchAPIResponse())

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response))

.andThen(doc => extractGames(doc))

So this new thing is only helpful for dealing with whatever PromiseIO wraps.

And, unfortunately, there needs to be a new one for whatever the new wrappable you come up with.

This is understandable to some extent, since each “external” wrappable would handle the functions

andThen and andThenWrap differently, so there can not really be a universal one.

Let’s see how we can create one for PromiseIO, step-by-step.

First things first, the skeleton of a transformer:

class PromiseIOT <A> implements Wrappable<A> {

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIOT<B> {

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): PromiseIOT<B> {

}

}

And the thing we wrap, which is a PromiseIO<A>:

class PromiseIOT <A> {

constructor(private readonly value: PromiseIO<Wrappable<A>>) {

}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIOT<B> {

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): PromiseIOT<B> {

}

}

And, as in case with PromiseIO itself, there has to be a way to run the promise (since it is wrapped).

We will simply expose the value we wrap - as unsafe as it might look, the value we wrap is a wrapped promise already:

class PromiseIOT <A> {

constructor(private readonly value: PromiseIO<Wrappable<A>>) {

}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIOT<B> {

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): PromiseIOT<B> {

}

runPromiseIOT(): PromiseIO<Wrappable<A>> {

return this.value;

}

}

Note how it has to be PromiseIO<Wrappable<A>> - so the value PromiseIO wraps is a Wrappable on its own.

This is where the transformers differ from the “simple” wrappers - if PromiseIO (the thing transformer wraps)

would wrap a simple type (PromiseIO<A>) - then there is no need for a transformer - just use the wrapper’ interface directly.

Now, to the implementation: the function passed to andThen and andThenWrap methods would be applied

to the thing the PromiseIO wraps. And the transformer wraps that PromiseIO object.

Hence we need to call this.value.andThen() to get to the value PromiseIO wraps.

But since that value is a wrapped type itself, we call andThen on it too:

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIOT<B> {

return new PromiseIOT(this.value.andThen(m => m.andThen(func)));

}

And when we want to return a new wrappable to be wrapped in a PromiseIO, we simply use andThenWrap on a nested-nested value:

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): PromiseIOT<B> {

return new PromiseIOT(this.value.andThen(m => m.andThenWrap(func)));

}

The whole transformer looks like this now:

class PromiseIOT <A> {

constructor(private readonly value: PromiseIO<Wrappable<A>>) {

}

andThen<B>(func: Func<A, B>): PromiseIOT<B> {

return new PromiseIOT(this.value.andThen(m => m.andThen(func)));

}

andThenWrap<B>(func: Func<A, Wrappable<B>>): PromiseIOT<B> {

return new PromiseIOT(this.value.andThen(m => m.andThenWrap(func)));

}

runPromiseIOT(): PromiseIO<Wrappable<A>> {

return this.value;

}

}

To incorporate it in the program:

const program = new PromiseIOT(fetchAPIResponse())

This won’t do, since fetchAPIResponse returns PromiseIO<string>, meaning it wraps the simple type.

And we need a Wrappable instead - otherwise we don’t need the transformer. Conveniently for us,

the next function in the chain takes that string value and returns a wrappable, ExceptionW<XMLDocument>.

So we can smash them together and pass to the PromiseIOT:

const program = new PromiseIOT(

fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response)

)

Now, there is one thing to recall from the previous wrappable we made, ExceptionW - the logic it wraps

will only be executed upon request. And we need to incorporate this request in the program.

Since our program so far looks the way it looks, it’s type is PromiseIOT, which does not have

a way to run ExceptionW it wraps. In fact, it does not even have an interface to do so,

since we have explicitly designed it to run all the operations on the doubly-nested type.

We do have one option, though - to run the ExceptionW right after we have fetched the response:

const program = new PromiseIOT(

fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response))

.andThen(ew => ew.runExceptionW<Either<Error, XMLDocument>>())

)

Note how we are not immediately running the logic wrapped by ExceptionW, but deferring it to the point in the future

when the Promise returns with the response (or failure). So the chain of function calls is still within

the restrictions of functional programming (or rather pure functions) mentioned in the beginning of this article.

Now the only thing left is to put the rest of the calls matching the types to the andThen or andThenWrap methods

and run the entire program:

const program = new PromiseIOT(

fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response))

.andThen(ew => ew.runExceptionW<Either<Error, XMLDocument>>())

)

.andThenWrap(doc => extractGames(doc))

.andThenWrap(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.andThen(game => printGame(game))

.runPromiseIOT()

.unsafeRun();

Leaving all the “boilerplate” code aside (all those wrappables), this is how our program looks like so far:

const fetchAPIResponse = (): PromiseIO<string> =>

new PromiseIO(() => fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`).then(response => response.text()));

const getResponseXML = (response: string): ExceptionW<XMLDocument> =>

new ExceptionW(

() => Either<Error, XMLDocument>.right(new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml")),

() => Either<Error, XMLDocument>.left(new Error('Received invalid XML'))

);

const createGame = (item: Element): Maybe<Game> => {

const rank = Maybe.option(item.getAttribute('rank'));

const name = Maybe.option(item.querySelector('name')).andThen(name => name.getAttribute('value'));

return rank.andThenWrap(r =>

name.andThen(n => ({ name: n, rank: r } as Game))

);

};

const extractGames = (doc: XMLDocument): Either<Error, Array<Game>> => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.reduce((accEither, item) =>

accEither.andThenWrap(acc =>

createGame(item)

.convert(

() => Either<Error, Array<Game>>.left(new Error('bad item')),

game => Either<Error, Array<Game>>.right([...acc, game])

)

),

Either.right<Error, Array<Game>>([])

);

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game>): Either<Error, Game> => {

if (games.length < 10) {

return Either<Error, Game>.left(new Error('Not enough games'));

}

return Either<Error, Game>.right(games[(Math.random() * 100) % 10]);

};

const printGame = (game: Game): void => {

console.log('RESULT', `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`);

};

const program =

new PromiseIOT(

fetchAPIResponse()

.andThen(response => getResponseXML(response))

.andThen(w => w.runExceptionW<Either<Error, XMLDocument>>())

)

.andThenWrap(doc => extractGames(doc))

.andThenWrap(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.andThen(game => printGame(game))

.runPromiseIOT();

program.unsafeRun();

Compare it to the initial implementation:

const fetchAPIResponse = () =>

fetch(`https://boardgamegeek.com/xmlapi2/hot?type=boardgame`)

.then(response => response.text());

const getResponseXML = (response: string) => {

try {

return new DOMParser().parseFromString(response, "text/xml");

} catch {

throw 'Received invalid XML';

}

};

const extractGames = (doc: XMLDocument) => {

const items = Array.from(doc.querySelectorAll('items item'));

return items.map(item => {

const rank = item.getAttribute('rank') ?? '';

const name = item.querySelector('name')?.getAttribute('value') ?? '';

return { rank, name };

});

};

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game>) => {

if (!games) {

throw 'No games found';

}

if (games.length < 10) {

throw 'Less than 10 games received';

}

const randomRank = Math.floor((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return games[randomRank];

};

const printGame = (game: Game) => {

if (!game) {

throw 'No game provided';

}

const log = `#${game.rank}: ${game.name}`;

console.log(log);

};

fetchAPIResponse()

.then(r => getResponseXML(r))

.then(doc => extractGames(doc))

.then(games => getRandomTop10Game(games))

.then(game => printGame(game))

.catch(error => console.error('Failed', error));

To me they both look quite similar. So was there any value in all this rewrite?

Let’s find it out together!

How about testing?

There is a big test suite for the initial implementation at the top of this article.

How do we go about testing this true-to-functional-programming version though?

We can apply it to this new code with few minor changes around assertions - now

instead of expecting an exception to be thrown or a value immediately returned,

we need to check if the value returned by the function is Left or Right and

check the wrapped value.

How about testing the program as a whole?

Well now, since the program is just a value, we can easily test its value.

Dang, by replacing the functions in the chain we can even test different behaviours

of the program! As in, instead of using fetchAPIResponse we can pass in a different

instance of PromiseIO wrapping a completely wild value and see how the program would

process it.

Errors are not a problem now - they are values, not breaking the execution of a program.

Interacting with the outer world is a breeze - just substitute the fetch with any Promise you want

and it still won’t break the whole program.

Now, here’s the catch: I am not trying to sell you functional programming as the Holy Grail of

developing the software and a silver bullet to every problem you might have.

In fact, there is a bug in the current true-to-functional-programming implementation,

which is way easier to pin-point with the “conventional” error logs in the console.

However, to find it, one first must run the program. With the functional-programming-implementation,

the program will simply result in a Either<Error, unknown>.Left value, without providing exact

reason for the error.

The bug is tiny but pesky:

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: Array<Game>): Either<Error, Game> => {

if (games.length < 10) {

return Either<Error, Game>.left(new Error('Not enough games'));

}

return Either<Error, Game>.right(games[(Math.random() * 100) % 10]);

};

Issue is in the games[(Math.random() * 100) % 10] expression:

(Math.random() * 100) % 10 is a floating-point number.

So most often, this will produce an undefined value.

And thus we come to the bigger issue, not related to the functional programming

itself, but rather the issue with TypeScript: in order for one to notice this issue,

the code must be run. But it would have not even been an issue if there was a mechanism

in place to prevent accessing the array elements by randomly typed index.

We can mitigate it in a similar manner we have dealt with all the problems in this whole

process of rewriting the program in a true functional programming way: implement a new

class which would wrap an array of elements of a same type and provide a reasonable

interface to access the elements.

Roughly put, if there was a class List<A> which would return a Maybe<A> when trying

to access an element of the list by index, the program would have looked differently:

const getRandomTop10Game = (games: List<Game>): Either<Error, Game> => {

if (games.length() < 10) {

return Either<Error, Game>.left(new Error('Not enough games'));

}

const game: Maybe<Game> = games.at((Math.random() * 100) % 10);

return game.toEither(

() => new Error('Bad game index in the list of games'),

(value) => value

);

};

And the whole program would have resulted in a Left<Error> with a message

rather than some misleading exception (with a stack trace, though).