Speeding-up algorithms with SSE

Have you ever asked anyone if assembly language might be useful nowadays? So, here’s the short answer: YES. When you know how your computer works (not a processor itself, but the whole thing - memory organization, math co-processor and others), you may optimize your code while writing it. In this short article, I shall try to show you some use cases of optimizations, which you may incorporate with the usage of low-level programming.

Recently I was reading through my old posts and found out there is a gap in the article about SSE - the post did not cover some of the implementation caveats. I decided to fulfill this and re-publish a new version.

Finding maximum

So, let’s start-off searching a maximum element in the array. Usually, it is nothing just iterating through the array, comparing each element with some starting value. For optimization reason and for the precision’s sake we set the initial value to the first array’s element. Like this:

float max_value(float *a, int n) {

float res = a[0];

for (int i = 1; i < n; i++) {

if (a[i] > res)

res = a[i];

}

return res;

}

Index-based search

What we could do firstly is to store not the search element itself, but its index:

float max_index(float *a, int n) {

int res = 0;

for (int i = 1; i < n; i++) {

if (a[i] > a[res])

res = i;

}

return a[res];

}

This naive optimization has its effect (time in seconds; the value found in braces):

Value-based: 0.00732200 (0.99999827)

Index-based: 0.00674200 (0.99999827)

Vector operations

This is quite a universal algorithm, which could be used for any type, which allows comparing. But let’s think abotu how we can speed up that code. First of all, we could split the array into pieces and find maximum among them.

There is a technology, allowing that. It is called SIMD - Single Instruction - Multiple Data Stream. Simply saying, it means dealing with multiple data pieces (cells, variables, elements) with the use of a single processor’ instruction. This is done in processor command extension called SSE.

Note: your processor or even operating system may not support these operations. So, before continuing reading this article, be sure to check if it does. On Unix systems you may look for mmx|sse|sse2|sse3|sse4_1|sse4_1|avx in /proc/cpuinfo file.

SSE extension has a set of vector variables to be used. These variables (on the lowest, assembly level, they are called XMM0 .. XMM7 registers) allow us for storing and processing 128 bits of data as it was a set of 16 char, 8 short, 4 float/int, 2 double or 1 128-bit int variables.

But wait! There are other versions of SSE, allowing for different registers of a different size! Check this out:

SIMD extensions

MMX - hot 1997:

- only integer items

- vectors have a length of

64 bits - 8 registers, namely

MM0..MM7

SSE highlights:

- only 8 registers

- each register has a size of 128 bit

- 70 operations

- allow for floating-point operations and vector’ elements

SSE2 features:

- adds 8 more registers (so now we have

XMM0..XMM15) - adds 144 more operations

- makes floating-point operations more precise

SSE3 changes:

- adds 13 more operations

- allows for horizontal vector operations

SSE4 advantages:

- adds 54 more operations (47 are given by SSE4.1 and 7 more come from SSE4.2)

AVX - brand new version:

- vector size is now

256 bit - registers are renamed to

YMMi, whileXMMiare the lower 128 bits ofYMMi - operations now have three operands -

DEST,SRC1,SRC2(DEST = SRC1 op SRC2)

SSE operations

So, I mentioned horizontal vector operations. But let’s do it in a series.

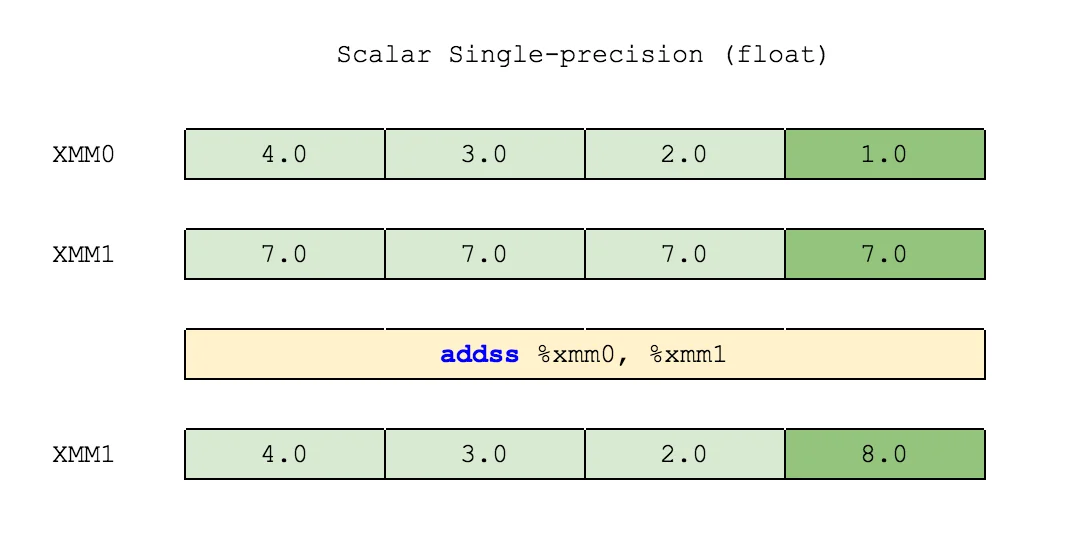

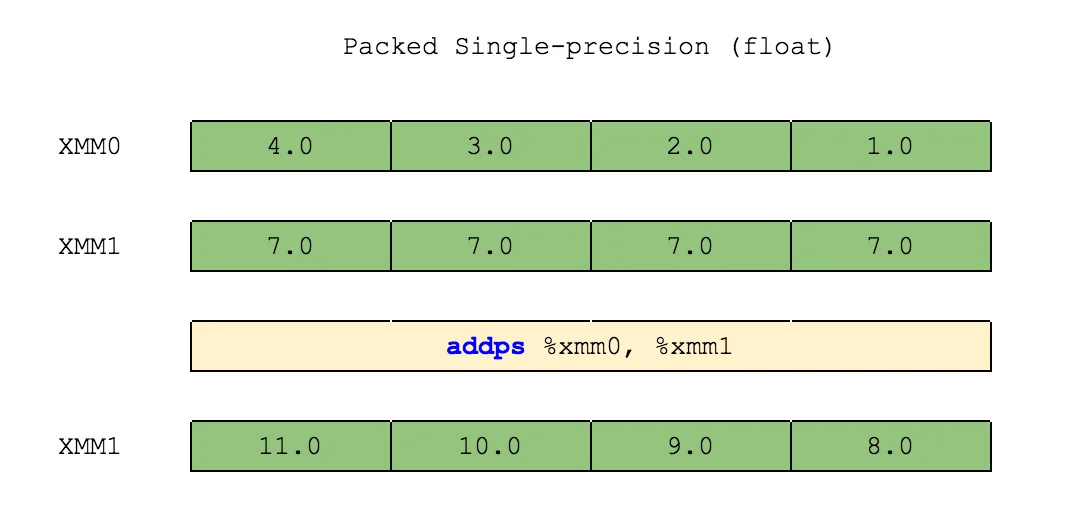

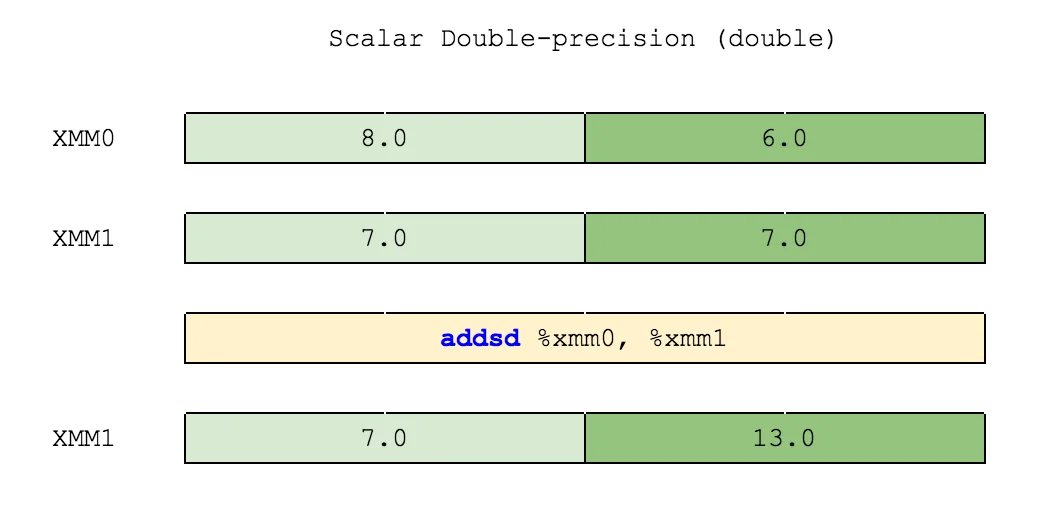

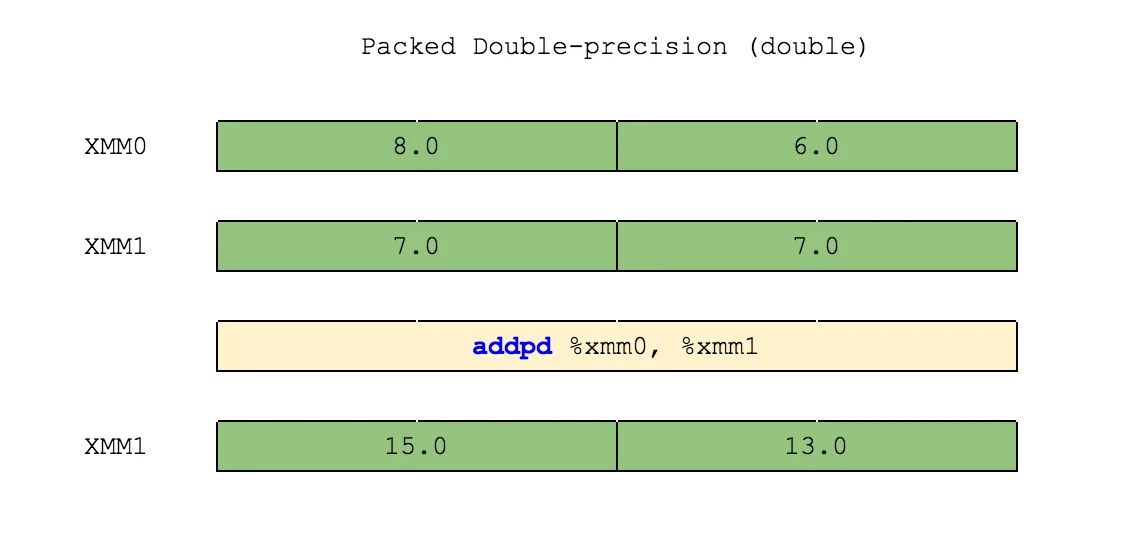

There are two SSE operation types: scalar and packed. Scalar operations use only the lowest elements of vectors. Packed operations deal with each element of vectors given. Look at the images below and you shall see the difference:

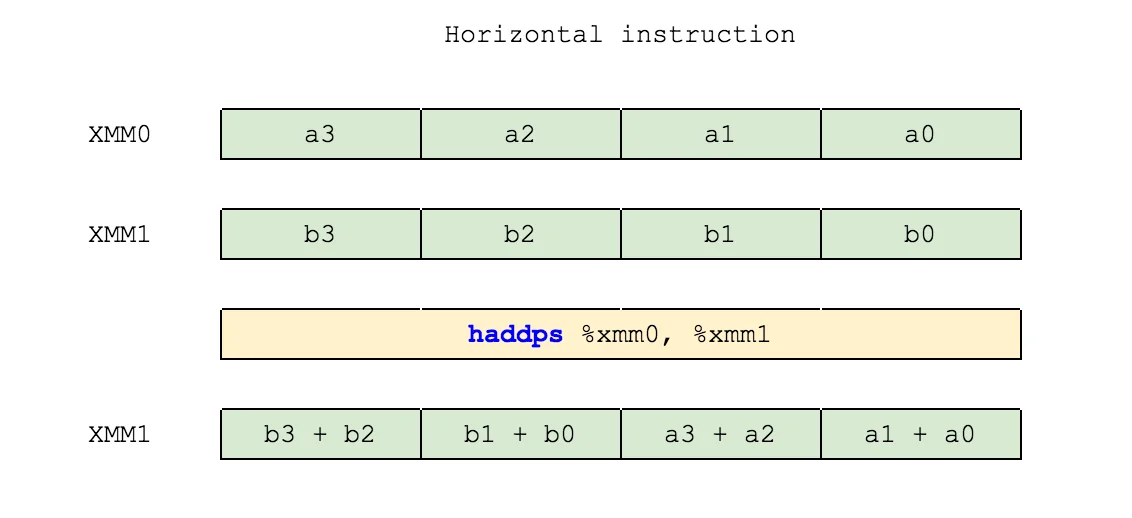

Horizontal operations deal on vectors in a different direction. Instead of operating on elements in the corresponding positions, these operate on elements in adjacent positions:

So there are six “types” of operations, as described above. They are:

- operations, dealing with scalar or double values

- operations, operating on all elements in a pack or on last elements of a pack

- operations, handling values on corresponding or adjacent positions

To determine if an operation type, you just need to look at the last two characters of operation’s name:

HADDPS -> Horizontal ADD Packed Single-precision

Working with SSE

Images above describe how processor instructions (assembly commands) work. To map those onto C++ functions, you only need to replace assembly operation with the corresponding function from SSE headers (I’ll cover that in just a second). But the main goal of those explanations above was to give you an idea how operations themselves work and where do they store results.

To work with SSE we need to follow these three steps:

- load data into XMM registers

- perform all the operations needed on those XMM registers

- store data from XMMs into usual variables

To use vector operations, you shall need to have some header files included in your code, as well as compiler flags, turned on.

These are header files:

mmintrin.h- MMXxmmintrin.h- SSEemmintrin.h- SSE2pmmintrin.h- SSE3smmintrin.h- SSE4.1nmmintrin.h- SSE4.2immintrin.h- AVX

None of the header files requires all the previous ones to be included too. Compiler flags are -mmmx, -msse, -msse2, -msse3, -msse4, -mavx, correspondingly. As with header files, none of these flags requires previous ones to be turned on.

Data types

There are three “standard” data types within SSE:

__m128, which is SSE’sfloat[4]__m128dcorresponds todouble[2]__m128irepresents one of these:char[16],short int[8],int[4]oruint64_t[2]

Each of them needs to be converted from or to standard C++ types with its own intrinsic (SSE operation).

Intrinsics

SSE operations in C++ are named this way: _mm_{OPERATION}_{SUFFIX}. The operation is the operation on vectors you want to perform. The suffix is a set of flags for a processor, showing in what way it should work with operands (packed/scalar, single-/double- precision, etc.).

For optimization’s sake, it is better if operands for intrinsincs are aligned in memory for base 16. But do not worry, the compiler will automatically decide if the variable is aligned or not and perform all the needed operations itself.

For loading data into SSE vectors there are four intrinsics:

_mm_set_ps(4.0, 3.0, 2.0, 1.0)->[4.0, 3.0, 2.0, 1.0]_mm_set1_ps(3.0)->[3.0, 3.0, 3.0, 3.0]_mm_set_ss(4.0)->[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 4.0]_mm_setzero_ps()->[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

And like those, there are very similar intrinsics for storing data from vectors in a usual C++ types (in the examples below assume working with the same __m128 t = [4.0, 3.0, 2.0, 1.0]):

_mm_store_ps(float[4], __m128)->[4.0, 3.0, 2.0, 1.0]_mm_store_ss(float*, __m128)->1.0_mm_store_ss(float*, __m128)->[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0]double _mm_cvtsd_f64(__m128d)->1.0int _mm_cvtsi128_si32(__m128i)->1(for given__m128i [4, 3, 2, 1])

Finding maximum

So, let’s get back to finding the maximum in an array. For this task we will search maximums on each 4 elements of our array, storing them in the XMMi register:

float max_sse(float *a, int n) {

float res;

__m128 *f4 = (__m128*) a;

__m128 maxval = _mm_setzero_ps();

for (int i = 0; i < n / 4; i++) {

maxval = _mm_max_ps(maxval, f4[i]);

}

_mm_store_ss(&res, maxval);

return res;

}

But if you run this code, you may notice it returns the maximum, not in 100% of cases. This is because we are storing four maximums between each portion of an array. So, only one of those four is the maximum. But how can we find the maximum among four numbers? Running a loop seems obvious but not effective enough…

We may use the shuffle intrinsic! That is, cycle-shifting vector three times and finding maximum between that shifted vector and its previous value. That will give us the maximum in all four positions of our vector.

Here is a better explanation:

If we want to cycle-shift a 4-number array, we use _mm_shuffle_ps intrisinc.

It takes 3 parameters: m1, m2, and mask. First two are four-word (four-number) packs. The mask consists of four numbers and shows which elements of pack m2 and which elements of pack m1 will form the result. This mask could be obtained using _MM_SHUFFLE(z, y, x, w) macro, which forms an integer according to the formula (z << 6) | (y << 4) | (x << 2) | w.

Given those definitions, the call m3 = _mm_shuffle_ps(m1, m2, _MM_SHUFFLE(z, y, x, w)) is equal to the formula m3 = (m2(z) << 6) | (m2(y) << 4) | (m1(x) << 2) | m1(w).

So we want to shift a pack by one element right, like this: [4, 2, 3, 1] => [2, 3, 1, 4]. We need to pass the initial pack, [4, 2, 3, 1] twice: _mm_shuffle_ps([4, 2, 3, 1], [4, 2, 3, 1], mask) and form a mask, which will use elements [2, 3] for the higher words of a result and elements [3, 1] for the lower words. These elements can be then indexed as follows:

+-----------+---------+

| index | 3 2 1 0 |

+-----------+---------+

| element | 4 2 3 1 |

+-----------+---------+

So to get the pair [2, 3] we need elements with indices [2, 1]. And to get the pair [1, 4] we need elements with indices [0, 3].

Given that, we can use macro _MM_SHUFFLE() to generate the mask: _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3). And the final formula looks like this: _mm_shuffle_ps(m1, m2, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3)).

+--+---------+

| | 3 2 1 0 |

+------------+

|m1| 4 2 3 1 |

+------------+

|m2| 4 2 3 1 |

+------------+

|m3| 2 3 1 4 |

+------------+

And our max function in pseudo-code looks like this:

// given val = [4, 2, 3, 1]

maxval = val;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

val = _mm_shuffle_ps(val, val, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3));

maxval = _mm_max_ps(maxval, val);

}

Which will be executed like this:

// preparation

maxval = [ 4, 2, 3, 1]

// i = 0

val = _mm_shuffle_ps(val, val, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3)) // = [2, 3, 1, 4]

maxval = _mm_max_ps([4, 2, 3, 1], [2, 3, 1, 4]) // = [4, 3, 3, 4]

// i = 1

val = _mm_shuffle_ps(val, val, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3)) // = [3, 1, 4, 2]

maxval = _mm_max_ps([4, 3, 3, 4], [3, 1, 4, 2]) // = [4, 3, 4, 4]

// i = 2

val = _mm_shuffle_ps(val, val, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3)) // = [1, 4, 2, 3]

maxval = _mm_max_ps([4, 3, 4, 4], [1, 4, 2, 3]) // = [4, 4, 4, 4]

The _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 1, 0, 3) call could be expanded to (2 << 6) | (1 << 4) | (0 << 2) | 3, which equals to 147 or 0x93 in HEX.

And here is the final C++ implementation:

float max_sse(float *a, int n) {

float res;

__m128 *f4 = (__m128*) a;

__m128 maxval = _mm_setzero_ps();

for (int i = 0; i < n / 4; i++) {

maxval = _mm_max_ps(maxval, f4[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

maxval = _mm_max_ps(maxval, _mm_shuffle_ps(maxval, maxval, 0x93));

}

_mm_store_ss(&res, maxval);

return res;

}

And how about integers?

The code for finding maximum with SSE among integer array is very, very similar to the previous one - you just need to decorate intrinsics with a different prefix and change store operation:

int max_sse_int(int *a, int n) {

int res;

__m128i *f4 = (__m128i*) a;

__m128i maxval = _mm_setzero_si128();

for (int i = 0; i < n / 4; i++) {

maxval = _mm_max_epi32(maxval, f4[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

maxval = _mm_max_epi32(maxval, _mm_shuffle_epi32(maxval, 0x93));

}

res = _mm_cvtsi128_si32(maxval);

return res;

}

Profit?

If we compare the results of all three methods - usual loop, index-based searching and SSE, we may see something like this (I ran these tests on my laptop’s i7 processor on one million random float/int values):

=== Looking for a maximum element in a list of 1000000 floats ===

* Value-based: 0.00382500 sec; max = 0.99999923

* Index-based: 0.00282200 sec; max = 0.99999923

* SSE: 0.00131300 sec; max = 0.99999923

=== Looking for a maximum element in a list of 1000000 integers ===

* Value-based: 0.00384200 sec; max = 99

* Index-based: 0.00298300 sec; max = 99

* SSE: 0.00130400 sec; max = 99

Here you can see that index-based searching gives some speeding-up (around 15%). But the real speed boost is gained with SSE (almost 4 times!).

Calculating the sum

Now let’s try something harder - calculating a sum of array’s elements. Here we will use the horizontal vector operations. But first, here’s the general algorithm:

float sum(float *a, int n) {

float res = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

res += a[i];

}

return res;

}

Simple enough, huh? Now let’s use the SSE’s _mm_add_ps intrinsic. Running it on each pack of four elements will give us the summary vector of four floats:

float sum_sse(float *a, int n) {

float res = 0.0;

__m128 *v4 = (__m128*) a;

__m128 vec_sum = _mm_setzero_ps();

for (int i = 0; i < n / 4; i++) {

vec_sum = _mm_add_ps(vec_sum, v4[i]);

}

_mm_store_ss(&res, vec_sum);

return res;

}

But if we now add the elements of that vector horizontally to themselves, we would then have the two-element vector. Adding it to itself will give us the final single-element vector:

float sum_sse(float *a, int n) {

float res = 0.0;

__m128 *v4 = (__m128*) a;

__m128 vec_sum = _mm_setzero_ps();

for (int i = 0; i < n / 4; i++) {

vec_sum = _mm_add_ps(vec_sum, v4[i]);

}

vec_sum = _mm_hadd_ps(vec_sum, vec_sum);

vec_sum = _mm_hadd_ps(vec_sum, vec_sum);

_mm_store_ss(&res, vec_sum);

return res;

}

Nice, isn’t it? But wait! Integers are available too! And they need their special intrinsics! Have no fear, nothing that different here, only the prefixes are different:

unsigned long long sum4(int *a, int n) {

unsigned long long res;

__m128i *f4 = (__m128i*) a;

__m128i vec_sum = _mm_setzero_si128();

for (int i = 0; i < n / 4; i++) {

vec_sum = _mm_hadd_epi32(vec_sum, f4[i]);

}

vec_sum = _mm_hadd_epi32(vec_sum, vec_sum);

vec_sum = _mm_hadd_epi32(vec_sum, vec_sum);

res = _mm_cvtsi128_si32(vec_sum);

return res;

}

And, just to approve our assumption of speeding-up, here’s the benchmarking (on one million of elements):

Value-based: 0.00853100 (500245.28125000)

SSE: 0.00319800 (500243.50000000)

Value-based on integers: 0.00773100 (49453512)

SSE on integers: 0.00274800 (49453512)

Now here is a thing to think about: the assembly output of the sum function is much shorter than the one for the sum_sse function:

sum(float*, int):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-24], rdi

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-28], esi

pxor xmm0, xmm0

movss DWORD PTR [rbp-4], xmm0

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 0

.L3:

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-8]

cmp eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-28]

jge .L2

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-8]

cdqe

lea rdx, [0+rax*4]

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-24]

add rax, rdx

movss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rax]

movss xmm1, DWORD PTR [rbp-4]

addss xmm0, xmm1

movss DWORD PTR [rbp-4], xmm0

add DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 1

jmp .L3

.L2:

movss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rbp-4]

pop rbp

ret

vs

sum_sse(float*, int):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 72

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-184], rdi

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-188], esi

pxor xmm0, xmm0

movss DWORD PTR [rbp-164], xmm0

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-184]

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-32], rax

pxor xmm0, xmm0

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16], xmm0

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-20], 0

.L5:

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-188]

lea edx, [rax+3]

test eax, eax

cmovs eax, edx

sar eax, 2

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-20], eax

jge .L3

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-20]

cdqe

sal rax, 4

mov rdx, rax

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-32]

add rax, rdx

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rax]

movaps xmm1, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-48], xmm1

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-64], xmm0

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-48]

addps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-64]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16], xmm0

add DWORD PTR [rbp-20], 1

jmp .L5

.L3:

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-80], xmm0

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-96], xmm0

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-80]

haddps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-96]

nop

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16], xmm0

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-112], xmm0

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-128], xmm0

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-112]

haddps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-128]

nop

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16], xmm0

lea rax, [rbp-164]

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-136], rax

movaps xmm0, XMMWORD PTR [rbp-16]

movaps XMMWORD PTR [rbp-160], xmm0

movss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rbp-160]

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-136]

movss DWORD PTR [rax], xmm0

nop

movss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rbp-164]

leave

ret

And yet, the performance of that longer piece of code is still higher!

Limitations?

Please note the difference between sums calculated with naive loop and the one calculated with SSE: they do differ. This is caused by a way computer work nowadays. Actually, how they store floating-point values. Since computers deal with binary system, they can not simply store all those digits after point in the memory and operate on them effectively.

Remember, how integers are stored in a binary system? Say, 14:

+-----------+------------------------+

| n | 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

+------------------------------------+

| pow(2, n) | 32 16 8 4 2 1 |

+------------------------------------+

| fits? | N N Y Y Y N |

+------------------------------------+

| 14 = | 0 + 0 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 0 |

+-----------+------------------------+

| bin(14) = | 0 0 1 1 1 0 |

+-----------+------------------------+

E.g. binary representation of 14 is: 142 = 001110. Leading zeroes could be skipped in a binary system (as there might be as many of those as you wish).

A similar thing happens to floating-point numbers: the difference is that computer stores the negative powers of two:

+------------+-----------------------------------------+

| n | 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

+------------------------------------------------------+

| pow(2, -n) | 0.03125 0.0625 0.125 0.25 0.5 1.0 |

+------------------------------------------------------+

| fits? | N N Y Y Y N |

+------------------------------------------------------+

| 0.9 = | 0 + 0 + 0.125 + 0.25 + 0.5 + 0 |

+------------------------------------------------------+

| bin(0.9) = | 0 0 1 1 1 0 |

+------------------------------------------------------+

As you can see, using 5 bits is not enough to represent 0.9, but only 0.875. Even if we use 32 bits (which is just a float data type in C), we will have 0.0110011001100110011001100110011102, which is 0.8999999999068677, but still, it’s not exactly what we wanted. On 64 bits (double type in C) it is better, 0.8999999999999999, but, again, not exact value. And if we try adding one million unprecise numbers, we will probably get the unprecise result.

Another big limitation of SSE is that initial data should be aligned to contain the number of elements, which is a multiply of either 2 or 4 (depending on the SSE operation type you are using - scalar or double).